Understanding historic suburbs

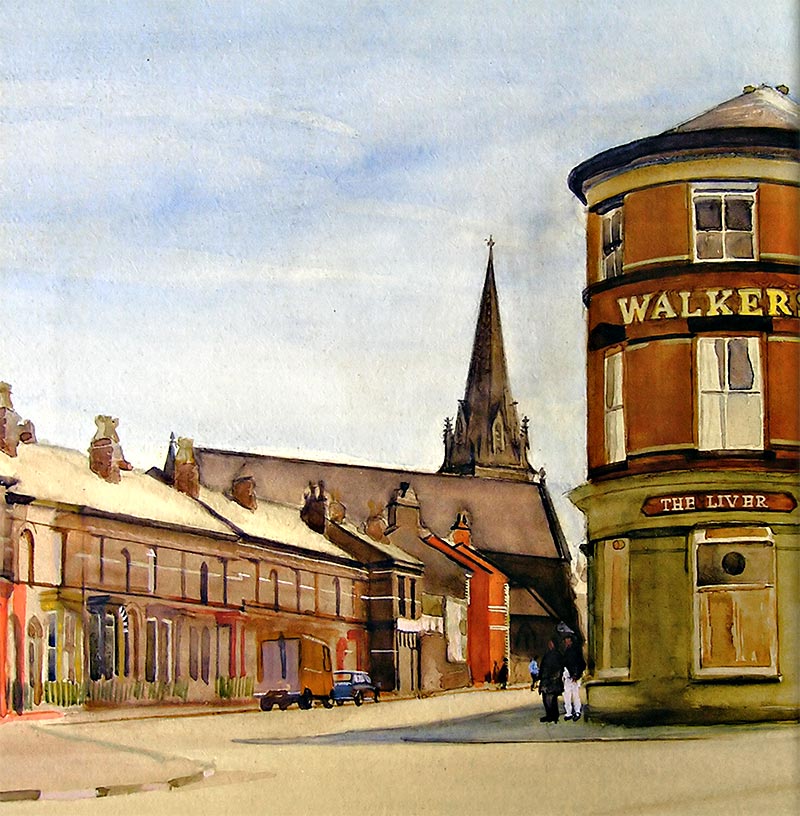

Figure 73 Frank Green, a local artist, has documented many buildings and street scenes in Anfield and Breckfield, often prompted by impending change. This detail of a watercolour, painted in 1971, shows the former Liver Hotel at the junction of Robson Street and Beacon Lane. The houses in Robson Street (left) survive, but St Cuthben's Church (1875-7), the hotel and Beacon Lane have disappeared.

[Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries LIC521]

Figure 74 Detail from Jonathan Bennison's Map of the Town and Port of Liverpool, with their Environs, 1835.Anfield and Breckfield are shown as a mixture of farmland and villa properties. The occupants of the principal houses are given. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]

Figure 75 Directories often contain street maps which give an indication of the progress of suburban development. This example, from Gore's Liverpool Directory, 1881, shows that many streets were only partially built up and some had yet to be developed. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]

Figure 76 Houses built on the former grounds of Bronte House were named after a series of architects: George Frederick Bodley (1827-1907), William Butterfield (1814-1900), George Goldie (1828-87), Edward Paley (1823-95) and William Eden Nesfield (1835—88) - or possibly his father, landscape architect William Andrews Nesfield (1793-1881). There are numerous similar clusters of themed street names in Anfield and Breckfield. [AA045555]

Figure 77 The Salisbury public house, Granton Road (built 1880s), commemorates Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903) and Conservative prime minister for three terms between 1885 and 1902, whose family owned a series of fields (on one of which Salisbury Road was laid out c!880) stretching from Walton Breck Road to Breckfield Road North. Building and street names are essential clues to understanding the development of the suburban landscape. [AA045080]

Figure 78 This watercolour by F Beattie shows Broadbent's cottages (see Fig 24a) as they appeared in 1911 - shortly before they were demolished. Unlike the Magenis view and the various map representations, Beattie's suggests that the cottages were stone built - a comparative rarity in the area.

[Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries, Beattie Collection 96]

Figure 79 19 Kemlyn Road, part of a whole street of 1880s houses photographed by Liverpool Corporation prior to demolition for the enlargement of Anfield football ground.

[Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries 352 HOU 111-9]

Figure 80 These designs by Richard Owens & Son for a new Sunday school behind the Richmond Baptist Chapel, dated 17 March 1930, are typical of the drawings deposited for the purposes of building control. In Liverpool, sadly, such drawings are scarce.

[Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries, Measured drawings, M720WDL-13-2-19]

Figure 81 Figure 81 (left) The wall dividing St David's Road from Stonehill Avenue poses an obvious question — why was it built? The development of different parcels of land by different owners left an earlier property boundary intact, but its retention in the form of a high brick wall is probably a deliberate form of social segregation: the houses in St David's Road, with their bay windows, are of a higher class than those in Stonehill Avenue. [DP027857]

Figure 82 Sybil Road, part of a series of streets named after the novels of Benjamin Disraeli, also demands answers. Why are the houses two-storeyed on one side of the road and three-storeyed on the other? Is it because the market for larger houses here was changing in the 1880s? [AA04S483]

This book has been concerned up to now with the history and character of one small area of Liverpool's extensive suburbs. Many other areas in Liverpool and elsewhere are of comparable interest and would amply repay the effort invested in researching their history. An understanding of the environment in which we live or work, or in which we or our forebears grew up, heightens our sense of place, allows us to appreciate and celebrate its best or most distinctive features, and may make us passionate in their defence. This knowledge need not be the rarefied preserve of academics and professionals. Indeed 'local history' has always been enriched by the dedication and intimate knowledge of local people. Once derided by the academic community, local history has made a serious contribution to research in recent decades, yielding detailed insights capable of sharpening our understanding of wider historical trends and arguably helping to democratise the study of history itself. The concluding section of this book sets out some of the ways in which anyone with the inclination to do so can learn more about the suburb of his or her choice. All that is required is an inquisitive outlook and perseverance.

This book has been concerned up to now with the history and character of one small area of Liverpool's extensive suburbs. Many other areas in Liverpool and elsewhere are of comparable interest and would amply repay the effort invested in researching their history. An understanding of the environment in which we live or work, or in which we or our forebears grew up, heightens our sense of place, allows us to appreciate and celebrate its best or most distinctive features, and may make us passionate in their defence. This knowledge need not be the rarefied preserve of academics and professionals. Indeed 'local history' has always been enriched by the dedication and intimate knowledge of local people. Once derided by the academic community, local history has made a serious contribution to research in recent decades, yielding detailed insights capable of sharpening our understanding of wider historical trends and arguably helping to democratise the study of history itself. The concluding section of this book sets out some of the ways in which anyone with the inclination to do so can learn more about the suburb of his or her choice. All that is required is an inquisitive outlook and perseverance.There are two main paths to understanding a suburb. One is to look at the suburban landscape itself - at the buildings, streets and other spaces of which it is composed and at the patterns which they create. The other is to make use of a variety of published and unpublished visual and documentary sources, many of which are easily consulted in local studies libraries and record offices (Fig 73). Looking at the landscape (commonly called 'fieldwork'), we see what has survived, and we see clues which help us to picture some, but not all, of what has been lost. We may be able to fill in some of the gaps in our knowledge by looking at the documents. These are particularly good at populating the landscape with real people, but even so they can offer no more than a series of snapshots over time, so inevitably there will be much that is untold here as well. The two approaches are complementary, however, and progress in one will usually allow more to be made of the other.

Before embarking on a study it is important to consider what you hope to know at the end of the process. If you simply want to know, in broad terms, when the suburb came into being, which parts emerged first, which at a later date, and what kind of landscape they replaced, then maps may provide all that is needed. If, however, you are interested in finding out who financed development, who built the houses, who occupied them and how they made their livings, a further range of documentary sources will be required. If you wish to know in detail how streets and buildings developed, how people used the buildings, how the social and economic status of occupants was reflected in the architectural character of their houses and how much of the past has survived in today's suburb, it will certainly be necessary to examine the physical landscape as well.

Even a cursory assessment of the suburb will benefit greatly from the evidence embodied in its buildings, streets and open spaces. By looking around us we can identify which kinds of building the suburb contains and the extent to which the housing is interspersed with commercial, institutional and industrial buildings. We may be able to identify particular zones where one or more non-residential categories of building are concentrated, or where houses of a particular type are found. Many building types are readily identifiable in the field from characteristic features or arrangements. Even without looking inside buildings it is usually possible to understand their internal arrangement in some detail simply by drawing inferences from the positions of doors, windows, chimneys, external plumbing and so on.

On a map, by contrast, they may only appear as so many undifferentiated shapes. We will get a clearer sense of the varied scale (vertically as well as horizontally), density and setting of the buildings and whether these variations are the result of deliberate contrivance - to emphasise the setting of a public building, for example - or the accidental consequence of piecemeal development. The occurrence of date-stones, coupled with some knowledge of architectural styles, will help to plot the chronological development of the suburb, but other signs, such as straight masonry joints and blocked openings, will alert us to the fact that many buildings have been altered since they were first built.

The degree of architectural ornament will prompt questions about the relative status of different streets, while the choice or arrangement of ornamental features may serve to associate scattered groups of buildings, since these features sometimes have the quality of a builder's signature. It will also begin to be apparent which are the characteristic features and motifs of buildings of a particular type and date, and whether these features survive in abundance or have been extensively eroded.

The most practical way to gather field data is through a combination of photography and note-taking. A printed pro-forma sheet, the headings serving as aides-memoirs, helps with consistency of approach, especially if more than one person is involved. The headings you adopt will depend on your interests and what you hope to achieve, so it is worth trialling a pro-forma before finalising it. But since not everything can be reduced easily to regimented headings, it is also important to leave space for unstructured notes. Some buildings will call for one pro-forma apiece, but where there is considerable uniformity a group - sometimes a whole street - may be covered. To accompany each pro-forma a single photograph may be all that is needed, but where possible front and rear views will provide a fuller picture and sometimes representative or unusual details will warrant further photographs. A similar approach can be adopted to other landscape features. It is also worth considering which photographs - general views, street scenes, etc. - will best convey the overall character of an area.

Aerial photographs literally give an overview - the National Monuments Record in Swindon has a huge public collection of recent and historic shots. It is likely that you will take quite a large number of photographs (with digital photography this need not be expensive) and to avoid confusion later it is important to keep a contemporaneous log of addresses or subjects.

Aerial photographs literally give an overview - the National Monuments Record in Swindon has a huge public collection of recent and historic shots. It is likely that you will take quite a large number of photographs (with digital photography this need not be expensive) and to avoid confusion later it is important to keep a contemporaneous log of addresses or subjects.A basic source for any research in the history of suburbs will be historic maps (Fig 74). Comparing the present-day landscape with progressively older maps - an exercise known as map regression - allows us to chart the physical growth of the built-up area and the impact of subsequent changes, as well as to identify features which may have been lost or radically altered, and elements of the pre-suburban landscape which have shaped its evolution. Large-scale maps (at a scale of 6in to one mile or greater) are of most use since they permit individual buildings to be distinguished.

Before the middle of the 19th century large-scale cartography was the preserve of professional surveyors who made estate maps for private clients, surveyed parishes or townships for administrative purposes such as enclosure or tithe apportionment, or produced town plans with a view to publication and sale. Their maps vary considerably in accuracy, scope and level of detail, but they are always worth examining and most will be available in local studies libraries or record offices.

The most comprehensively available large-scale maps are those published by the Ordnance Survey from the 1840s onwards (see Fig 10). Coupled with the magnificent town plans (at scales up to 1:500), these depict a greater range of detail than all but the very best productions of independent surveyors, but the interval between successive editions may amount to many years. For example Lancashire, to which Liverpool belonged until 1974, was the first county to benefit from six-inch mapping, with Liverpool and its environs being surveyed between 1845 and 1849, but Anfield and Breckfield had to wait until 1890 for the first maps at the larger scales of 1:2,500 and 1:500 to be surveyed.

Other maps may help to fill in the gaps (Fig 75), though one effect of the Ordnance Survey's massive programme of large-scale mapping was to reduce very considerably the opportunities for professional surveyors in this field.

Maps allow us to visualise the layout and, depending on the map scale, the plot sizes and plan-types of an area. Much may be deduced from the ways in which streets and boundaries relate to each other, whilst place names and street names contain many clues to their origins (Figs 76 and 77). But maps generally show only the two-dimensional layout of the suburb; most large-scale maps do not even include contours, which help us to visualise the lie of the land. To see what it actually looked like, and to glimpse the emotional response of past generations, we turn to the work of topographical artists and photographers.

Actuated by the prospect of change, writers, artists and photographers often record features of antiquarian interest or picturesque appeal (Fig 78; see also Figs 4, 12, 18, 24a, 41a and 73), and sometimes they document building work in progress. Much of their work can be found in local galleries, museums and libraries, though items scattered further afield can be hard to locate. Local newspapers sometimes printed detailed accounts of the opening of major buildings and many have generated extensive photographic archives.

Directories are another invaluable source, helping us to relate the physical form of an area - the size, type, elaboration and density of houses and other features - to the social and economic composition of the neighbourhood at different dates. Trade directories were produced for some major towns in the 18th century, and during the 19th century coverage extended to every town and village in the land. Liverpool's earliest directory appeared in 1766 and Gore's Liverpool Directory, which first appeared the following year, appeared more or less every two years from 1805. Directories were commercial publications and their contents reflect what was judged to be commercially useful information at the time.

Early suburbs, often beyond the municipal boundaries of the day, were at first poorly served. The initial almost exclusive emphasis on merchants and professional people gradually expanded to include lesser tradesmen, craftsmen, churchmen, public and private officials, and private individuals above a certain social level. By the late 19th century coverage of a large city such as Liverpool was comprehensive enough to include a substantial proportion of the working-class population, but the very poor make only sporadic appearances. The ways in which the information was presented also proliferated over time. Early trade directories listed individuals alphabetically and gave rudimentary addresses, usually no more than the street in which the individual's business was located.

Later examples also grouped the names by occupation, allowing the distribution of trades and industries to be plotted much more easily, and in addition, in the larger towns and cities, listed them street by street. These street directories usually allow the occupants of individual houses to be quickly and confidently identified, though changes to street numbering can cause problems. Even at their most complete, however, directories normally list only the head of the household; other household members - including many elderly people, wives, children, lodgers and servants - rarely appear.

For a more developed understanding of the social composition of households, streets and areas, the records of the national census are invaluable. Since 1801 the census has been taken by Government every ten years except in 1941, but the information recorded before 1841 was too brief to be of much assistance for this kind of research. Moreover, detailed census returns remain confidential for 100 years, so the latest census currently available for use is that of 1901. The ease with which census information can be confidently related to individual buildings varies, but where this objective is achieved a much more rounded picture of life in the Victorian suburb emerges. But to understand how people felt about their own environment in the past the most fruitful approaches will be through oral history (for recent decades) or the more intimate records left behind in diaries and journals, such as the diary of David Brindley in 1880s Everton (see References and further reading).

Other record types yield more detailed information on individual properties. Property deeds are concerned essentially with ownership, including leases, rather than occupation. Often still in private hands, they may extend as far back in time as the original development of the suburb, providing clues to who was actively involved in the development process, and they may recite deeds going back still further, shedding light on the pre-suburban landscape. They rarely state exactly when streets were laid out or buildings erected, but they will often point to a limited span of years during which the land was developed.

Local authority records are often extensive. Rate books survive for many towns, sometimes from before the 19th century. They record occupancy and rateable value on an annual basis and sometimes give telling details about the size and nature of the property being assessed. From the mid-19th century onwards many local authorities photographed buildings (Fig 79), including slum properties earmarked for demolition.

Building control plans were required by local authorities to ensure that new buildings, and certain alterations to existing ones, met the standards enshrined in building by-laws, the precursors of modern building regulations. Different authorities made them mandatory at different times, but generally large towns and cities, where the problems caused by sub-standard buildings aroused most alarm, were quickest to adopt the practice. The resulting records typically consist of floor plans, drainage plans, sections and elevations. The name of the architect or builder, as well as the owner, often appears either on the drawings or in the register recording their deposition, together with the date of submission and the date of approval. Building control plans are an invaluable indication of an architect's or builder's declared intention, though the existence of approved plans does not guarantee that the building concerned was actually constructed, nor, if it was, that it adhered in all particulars to the deposited plans. The survival of these documents is erratic and sadly those for Liverpool appear, with a handful of exceptions, to be lost (Fig 80). Many other local authority records, including those concerned with public health and public institutions such as schools, are potentially valuable, as are church records.

Except where very small areas are being studied it is unlikely that all of the sources described here will be fully exploited. The sheer quantity of available information is vast, and consulting sources can be very time consuming. The most pragmatic approach will often be to examine them with particular questions in mind once you have built up a preliminary impression of the main lines of development (Figs 81 and 82). Merely describing the sources available for study does not, of course, reveal how we come to an understanding of the historical evolution, form and character of historic suburbs. The gathering of field and documentary evidence needs to be followed by careful analysis if its full potential is to be realised. There is a real danger that the accumulation of facts may obscure the main threads of the narrative; much better to concentrate on identifying patterns in the data and explaining their causes and meanings. Existing studies of other areas will often suggest fruitful approaches.

A useful and widely applicable technique is that of 'sampling'. Your initial analysis (using maps, fieldwork and existing histories) will have charted the main lines of chronological development and geographical variations in the character of the area. You may wish to know how and why these patterns have emerged, and what they meant for those whose lives were shaped by them. Ask yourself which are the key developments - they may be pioneering, or typical of a particular period, or special for one reason or another - and look for the examples that best help you to understand them. Well-preserved or well-documented examples are especially valuable and if examined carefully will often provide the answers you need without having to probe every instance in detail. You will then be able to make cautious generalisations about the wider picture.

Finally, having established the origins and development of the area it is helpful to consider the significance and value of what survives. This is inevitably a subjective exercise but it should be an important consideration in determining the future of the area. For some, notions of historical and architectural importance will be a touchstone. Buildings may be protected by placing them on the Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest provided they meet certain national criteria, but buildings of only local significance can now be formally acknowledged in local development frameworks through the compilation of 'local lists'. Other people will champion aesthetic considerations, which may in part reflect the present state of repair of properties; others again may see value only in those things that demonstrably fulfil a local need, or which can be restored to beneficial use at reasonable cost. One way of exploring the diversity of local opinion is to ask a number of people each to photograph the ten buildings that matter most to them and to explain the reasons for their choices. Reconciling not only these points of view but those of planners, developers, employers and visitors can be difficult, but a number of questions may bring matters into focus. How did the area evolve? Is everything that survives of much the same date or can phases of development be identified? What is the significance of the various phases of evolution? What types of building and open space does the area exhibit and how are they arranged? Are the resulting landscapes commonplace or unusual? Do they survive much as designed or have they been extensively altered, and are any alterations of interest in their own right? Which elements (building types, materials, stylistic motifs, etc) are distinctive of the locality? Which individual features or buildings are important to illustrate the area's development or preserve its character and to what extent is their importance dependent upon the physical context of neighbouring buildings or spaces? Which buildings and spaces do people enjoy for the contribution they make to the local scene? Which might meet the same test with appropriate investment and refurbishment? Are there buildings which might be lost with no detriment to the area?

Finally, make your findings known through community engagement, publication (traditional or web-based), deposit in a local library, talks to local societies and so on. Sound research and well-documented community views should be vital considerations in decision-making when changes to the character of an area are proposed. Change is inevitable, and often desirable, but change that recognises the value of what is already there and of what the past may yet contribute to the future is more likely to lead to the creation of sustainable communities - of places where people want to live and work, places that they will feel pride in. As in our lives, so in the places we inhabit, a sense of identity, rooted in knowledge of where we have come from and what has shaped us, is invaluable.

This book is not the product of exhaustive research or detailed surveys. Instead it is an illustration of what can be achieved relatively quickly by examining a range of physical and documentary source materials with particular questions in mind. The intention has been to demonstrate the interest and complexity of an apparently ordinary suburb, elucidating the meaning of a half-forgotten historic landscape, exploring its significance and prompting debate about its value in the future.

« Previous Top Home Pictures »