Inroduction:

suburbs and history

Figure 1 Our understanding of the more densely packed suburbs, built to house ordinary men and women in the 19th century, has been conditioned by rising aspirations which have outstripped the modest ambitions of the suburbs 'first inhabitants, and by journalistic perceptions of the 'inner city' as a zone in crisis. [NMR 20747135]

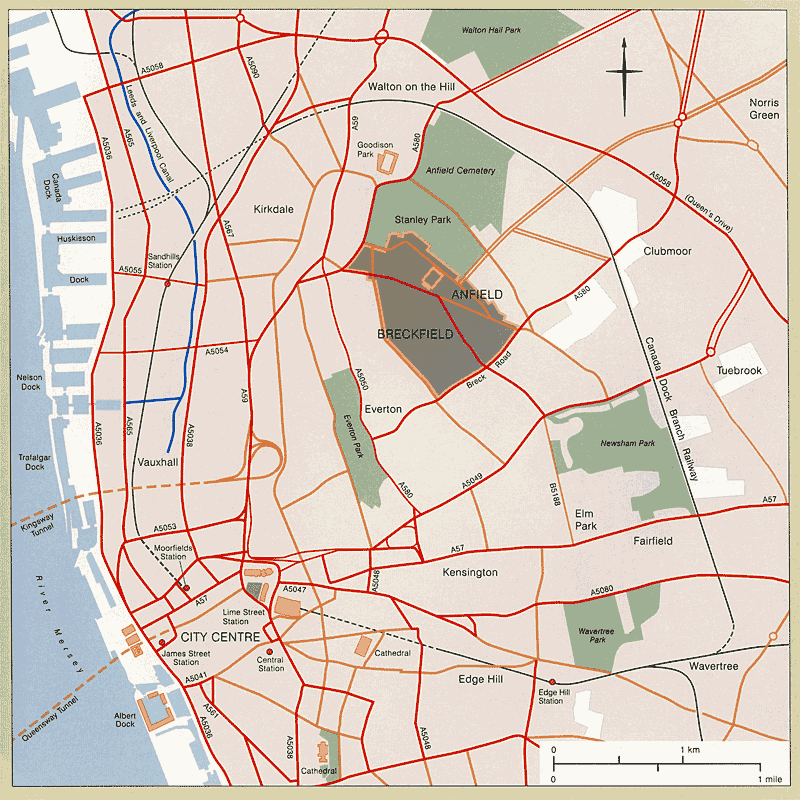

Figure 3 Anfield and Breckfield in relation to central Liverpool and the docks, the earliest of which were close to the centre. Everton,just south-west of Breckfield, developed as a villa suburb in the late 18th century but as the docks spread northwards (Trafalgar Dock opened in 1836, Canada Dock in 1859) it began to fill with working-class housing, prompting villa builders to look inland for suitable sites.

The transformation of 19th-century England into a predominantly urban society, first recorded in the 1851 census, was acknowledged by contemporaries as a momentous phenomenon. Unprecedented population growth combined with rapid urbanisation resulted in many towns and cities spectacularly overflowing their historic boundaries. Outside London the major growth centres were the manufacturing towns of the Midlands and the North, and those commercial centres such as Liverpool that profited from the associated increase in trade. Early growth, much of it fuelled by migration from the countryside, was absorbed in part by existing housing, and in part by piecemeal growth and infilling. The result, all too often, was severe overcrowding, insanitary conditions and disease.

The transformation of 19th-century England into a predominantly urban society, first recorded in the 1851 census, was acknowledged by contemporaries as a momentous phenomenon. Unprecedented population growth combined with rapid urbanisation resulted in many towns and cities spectacularly overflowing their historic boundaries. Outside London the major growth centres were the manufacturing towns of the Midlands and the North, and those commercial centres such as Liverpool that profited from the associated increase in trade. Early growth, much of it fuelled by migration from the countryside, was absorbed in part by existing housing, and in part by piecemeal growth and infilling. The result, all too often, was severe overcrowding, insanitary conditions and disease.Increasingly, those who could afford to looked beyond the old confines of the town for a more attractive place to live. Typically the wealthiest moved first, but as conditions in the towns deteriorated successive strata of urban society, each a little less wealthy than the previous one, followed suit. The resulting demand for housing was met by landowners releasing land for sale or development. By the end of the 19th century suburbs of one kind or another housed a large and rapidly growing sector of the population, while the population of town centres was falling. Both trends continued well into the 20th century; only within the last 15 years or so has government planning policy decisively reversed the population decline of some urban centres.

England's suburbs result directly from the processes of industrialisation and urbanisation through which the modern nation was forged (Fig 2). Spreading out over hundreds of square miles of former agricultural land they are the horizontal counterpart of the towering cotton mills and dock warehouses which, for a century or more, symbolised Britain's industrial and trading might. Although growth -at least until the First World War - was achieved almost entirely through private enterprise, such a rapid expansion of the housing stock was not accomplished without a degree of standardisation. From the 1840s municipal authorities framed increasingly stringent building by-laws to ensure that the damage inflicted by largely unregulated development in the early industrial era was not repeated. Such by-laws sought to raise the standard of living for ordinary people by specifying such things as sound building construction and sanitation, and adequate space, light and ventilation, and by segregating industrial and other activities injurious to health. Acting alongside certain practical and economic constraints, by-laws disposed builders in favour of particular house types, especially the terraced house with its typically narrow frontage and deep plan. The resulting streetscapes exhibit a degree of uniformity which is eloquent of both the pressing needs of a fast-growing and modernising economy and of the increasing consolidation of society around common values of rational planning, decency and public health.

'Standardisation' is a reminder of that most persistent criticism of the suburb: that it is dull, repetitive and uninspiring, lacking the pent-up vigour and excitement of the urban scene as much as it does the spaciousness, tranquillity and proximity to nature of the countryside. Both town-dwellers and country-dwellers are prone to endorse the stereotype and a superficial acquaintance with some suburbs may seem to confirm its validity. But a closer look will usually reveal considerable variety, the result in part of piecemeal development prolonged over many years, and in part of the intensely stratified nature of 19th- and early 20th-century society, which found expression in countless ways of differentiating wealth and status. Suburbs also vary in appearance according to the building materials and architectural styles employed.

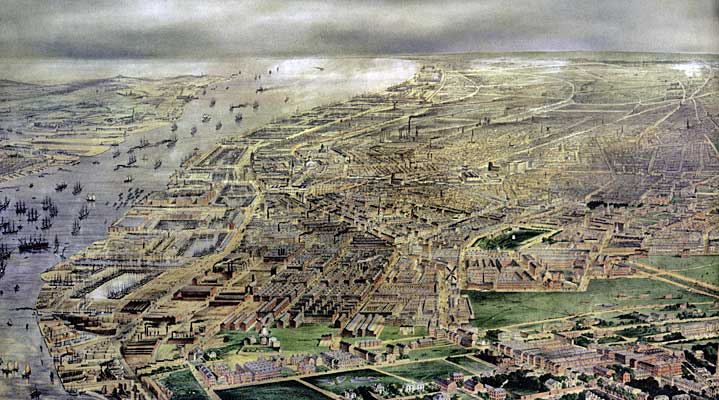

Figure 2 John Isaac's Aerial View of Liverpool, 1859, vividly illustrates how the expansion of the docks, principally northwards to the mouth of the Mersey, drew urban development in its wake. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]

'Standardisation' is a reminder of that most persistent criticism of the suburb: that it is dull, repetitive and uninspiring, lacking the pent-up vigour and excitement of the urban scene as much as it does the spaciousness, tranquillity and proximity to nature of the countryside. Both town-dwellers and country-dwellers are prone to endorse the stereotype and a superficial acquaintance with some suburbs may seem to confirm its validity. But a closer look will usually reveal considerable variety, the result in part of piecemeal development prolonged over many years, and in part of the intensely stratified nature of 19th- and early 20th-century society, which found expression in countless ways of differentiating wealth and status. Suburbs also vary in appearance according to the building materials and architectural styles employed.

Figure 2 John Isaac's Aerial View of Liverpool, 1859, vividly illustrates how the expansion of the docks, principally northwards to the mouth of the Mersey, drew urban development in its wake. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]These change over time, but they also differ from place to place, conferring a badge of individuality or local character on an area. In fact careful scrutiny of any particular suburb will reveal that an environment which we have long felt to be familiar still has the capacity to surprise us and challenge our preconceptions.

This book focuses on a suburban district of Liverpool and explores the nature, significance and value of the 'ordinary' in the historic environment. Now part of Liverpool's inner-city suburbs, the district embraces portions of the modern wards of Anfield and Breckfield, just over a mile (2km) north-east of central Liverpool and east of Everton (Fig 3). There are many areas of equal interest in Liverpool and elsewhere. The reason for looking at this one in particular is that in 2003 a large proportion of Anfield and Breckfield was designated as a target area under the Government's Housing Market Renewal Initiative, which envisages a combination of clearance, refurbishment and new housing and infrastructure as a vehicle for economic and social regeneration. These plans are already being implemented and are likely to change the area dramatically. English Heritage urges that in such circumstances an audit of the historic environment is essential to assess both the historic interest of the affected area and its potential to underpin a wider process of regeneration. This position has been endorsed by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), the government department responsible for the Initiative. But the historic environment is not the only consideration. Change on the scale envisaged must reflect a wider balance of needs, aspirations, opportunities and resources, and if it is to deliver long-term, sustainable benefits it must command the support of those who will live and work in the area for years to come.

This book focuses on a suburban district of Liverpool and explores the nature, significance and value of the 'ordinary' in the historic environment. Now part of Liverpool's inner-city suburbs, the district embraces portions of the modern wards of Anfield and Breckfield, just over a mile (2km) north-east of central Liverpool and east of Everton (Fig 3). There are many areas of equal interest in Liverpool and elsewhere. The reason for looking at this one in particular is that in 2003 a large proportion of Anfield and Breckfield was designated as a target area under the Government's Housing Market Renewal Initiative, which envisages a combination of clearance, refurbishment and new housing and infrastructure as a vehicle for economic and social regeneration. These plans are already being implemented and are likely to change the area dramatically. English Heritage urges that in such circumstances an audit of the historic environment is essential to assess both the historic interest of the affected area and its potential to underpin a wider process of regeneration. This position has been endorsed by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), the government department responsible for the Initiative. But the historic environment is not the only consideration. Change on the scale envisaged must reflect a wider balance of needs, aspirations, opportunities and resources, and if it is to deliver long-term, sustainable benefits it must command the support of those who will live and work in the area for years to come.Anfield is known to millions around the world as the home of Liverpool Football Club and the approaches to the stadium are familiar to the thousands who regularly attend matches there, but the origins, development and architectural character of Anfield and Breckfield have never been explored in detail. They have their own story to tell about the evolution of a particular landscape; they tell us much about the development of Liverpool, once the nation's foremost provincial seaport and still a city of international renown; and they can enlighten us about factors influencing the development of suburbs all over England. The purpose of this book is to explore these intertwined strands of Liverpool's, and the nation's, past and to draw attention to the ways in which everyone can understand and appreciate a characteristically English historic environment that becomes, day by day, less and less ordinary.

« Pictures Top Home Next »