Terrace upon terrace

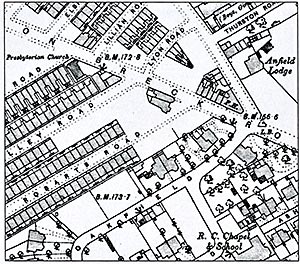

Figure 25 (far right ») By 1890 the area was very largely built up, as shown on Philip's New Map of Liverpool and its Environs, 1891 (compare with Fig 10). The few remaining areas of vacant land were nearly all built on by 1905. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]

Figure 26 The offices of the Liverpool & London Insurance Company (architect C R Cockerell, 1856-8) in Dale Street. In the 1860s the firm's manager, William Wilks, lived at Mill Bank,Anfield Road (see Fig 21). [AA040746]

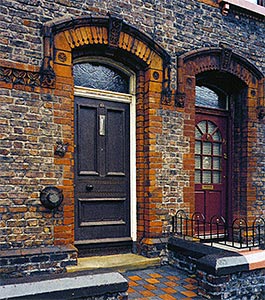

Figure 27 (right ») This terrace, 60-94 St Domingo Vale, was built from the late 1860s to the early 1870s. The houses, though substantial, marked the collapse of the villa ideal in Breckfield. [AA045537]

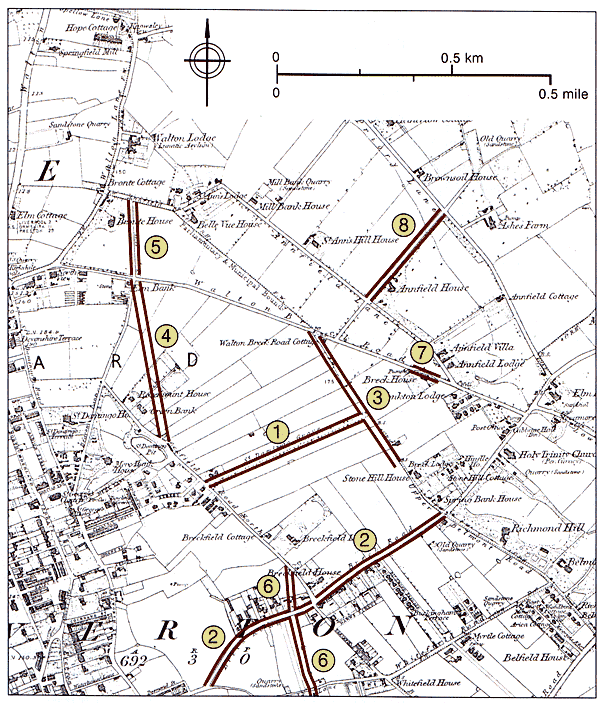

Figure 28 By plotting different building types on a map we reveal something of the social makeup of the area. This map (showing the area as it appeared in 1905) shows how houses of different sizes and status tended to be built in distinct areas. The villas duster in groups and the larger terraced houses nearly all occur close to them. The map also shows how residential and commercial property were segregated, with the latter largely confined to the main thoroughfares.

Figure 29 Grasmere Street, part of the 'Lake District' behind Breck Road, was laid out before 1865 and built up in the early 1870s. These houses are among the earliest small terraced houses in Breckfield. [AA045535]

Figure 30 Anfield and Breckfield were transformed by residential development - major improvements to the network of country lanes were called for. St Domingo Grove, the first major new street, was a private initiative, but the remainder were municipal enterprises.

1 St Domingo Grove, laid out by 1845

2 Breck Road, widened c1865

3 Oakfield Road, new road 1868

4 Robson Street, new road 1870-3

5 Sleepers Hill, widened c1873

6 Queen's Road, new road by 1875

7 Walton Breck Road, straightened c1890

8 Arkles Lane, widened c1906

[Based on the 1851 Ordnance Survey 6-in map, surveyed 1845-9]

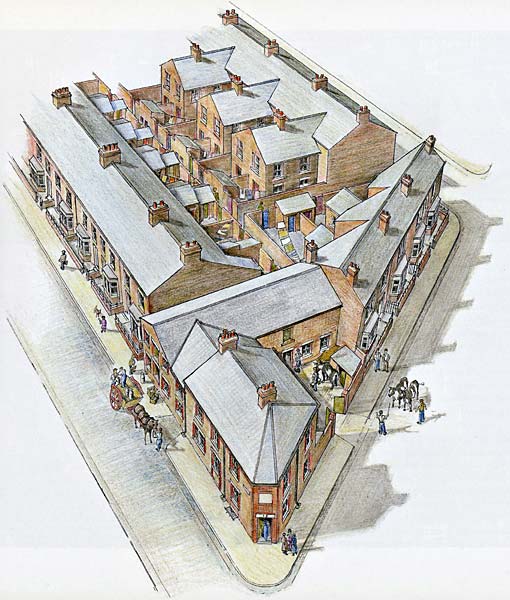

Figure 31 (below) The junctions of Walton Breck Road (bottom right) with Valley Road (bottom left) and Dinorwic Road show how the preferred rectangular geometry of terraced development was adapted to local conditions. The awkward carrier site was occupied by a town dairy and its yard. Comparison with Fig 6 shows that although this was a densely built-up landscape, individual households enjoyed privacy, hygiene and space for such things as drying clothes, to an extent undreamt of by court and cellar dwellers.

Figure 33 - right: Handfield Street (left) and Sockbridge Street (right), both late 1880s, converge at an acute angle - one consequence of developing a triangular parcel of land. [NMR 20747160]

Figure 35 - right: 70 & 72 Rockfield Road, built early 1880s, typify the more generous two-storey terraced house: forecourted, with a canted bay and two first-floor windows. [AA045484]

Figure 36 - far right: Two type of paired 'outriggers' to the rear of 82-96 Rockfield Road (early 1880s). The more distant examples are large three-storey gabled rear ranges; the nearer examples are small two-storey lean-tos. Other houses have small outshots, often with a shallower roof pitch than the main part of the house. [AA045486]

Figure 37 - far right: Double-fronted terraced houses such as 250, 252, and 254 Anfield Road, built in the 1890s, are rare, but made the most of shallow plots lining a prestigious street. The alternation of canted and square bay windows is characteristic - the former for the parlour, the latter for the dining room. [AA045504]

Figure 38 - right: Houses in Venmore Street - named after the Welsh Venmore family of builders & estate agents - have narrow plans but benefit from an attic storey. [AA045544]

Figure 39a: Some striking effects were achieved in the 1880s by extending simple brick patterns across a whole terrace, as here at 60-66 Granton Road. [AA045540]

Figure 39b: Modern owners have often preferred individuality, as at 45-55 Herschel Street. [AA045543]

Figure 40: 25 Arkles Road illustrates the range of mass-produced terracotta ornament available to the builder by the 1880s. The original iron railings to the forecourt walls are lost, but other details, including the panelled door and under-floor ventilation grille, remain. [AA045520]

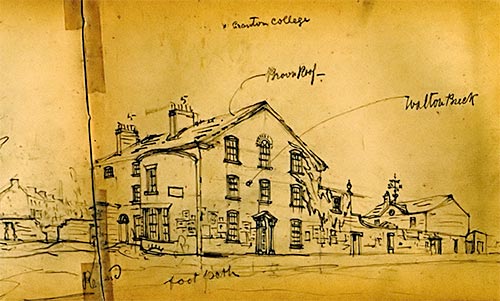

Figure 41a: This view (right), sketched by Hugh Magenis between 1886 and 1888, shows Breck House, also known as Walton Breck, a late 18th-century villa on Walton Breck Road. The evidence that bill-posters have been active suggests that the house is empty and about to be demolished. The newly built terrace beyond foreshadows the fate of the older house. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries Hq 741.91 MAG]

Figure 41b: The Ordnance Survey map of 1893 (surveyed 1890) shows Breck House as a forlorn island (upper centre), subdivided and shorn of its name and garden, the streets around it laid out and the pavement already realigned in anticipation of its passing. William Tristram of Breck House initiated the proposal for Holy Trinity Church in 1844; his successor at the property was prompted to sell up when The Breckside public house (now The Flat Iron, marked 'PH.') opened a few yards away on the opposite side of the road

By the middle of the 19th century Liverpool was growing at an unprecedented rate (Fig 25). The trade of the port outgrew the existing docks, which expanded northwards by leaps and bounds. The docks employed thousands of casual labourers whose precarious conditions of employment and poor rates of pay compelled them to live as close as they could to their place of work. But they also employed hundreds of stevedores and warehousemen, whose work was regulated by port officials and government excisemen, while the railway companies, whose sidings threaded their way onto the waterfront, employed a further range of functionaries in similarly responsible positions. All these typically chose to live apart from the poorer labourers. There was also a rapidly growing commercial and insurance sector, intimately linked to shipping and the merchandise handled in the docks, but increasingly divorced from the physical circumstances of trade, occupying opulent chambers or offices in central Liverpool (Fig 26). In an age of manual bookkeeping, lacking the computer or the photocopier for assistance, these businesses relied upon thousands of clerks to keep their accounts and record their correspondence with clients. A growing population required the services of an ever-increasing multitude of craftsmen, tradespeople and public servants and they, like everyone else, looked to the suburban fringes of Liverpool as soon as their means allowed. Speculative builders were quick to respond and by the 1860s even once-exclusive Everton was, in the words of a near-contemporary, 'as dingy and commonplace as the town', so builders turned to more distant neighbourhoods such as Anfield and Breckfield.

By the middle of the 19th century Liverpool was growing at an unprecedented rate (Fig 25). The trade of the port outgrew the existing docks, which expanded northwards by leaps and bounds. The docks employed thousands of casual labourers whose precarious conditions of employment and poor rates of pay compelled them to live as close as they could to their place of work. But they also employed hundreds of stevedores and warehousemen, whose work was regulated by port officials and government excisemen, while the railway companies, whose sidings threaded their way onto the waterfront, employed a further range of functionaries in similarly responsible positions. All these typically chose to live apart from the poorer labourers. There was also a rapidly growing commercial and insurance sector, intimately linked to shipping and the merchandise handled in the docks, but increasingly divorced from the physical circumstances of trade, occupying opulent chambers or offices in central Liverpool (Fig 26). In an age of manual bookkeeping, lacking the computer or the photocopier for assistance, these businesses relied upon thousands of clerks to keep their accounts and record their correspondence with clients. A growing population required the services of an ever-increasing multitude of craftsmen, tradespeople and public servants and they, like everyone else, looked to the suburban fringes of Liverpool as soon as their means allowed. Speculative builders were quick to respond and by the 1860s even once-exclusive Everton was, in the words of a near-contemporary, 'as dingy and commonplace as the town', so builders turned to more distant neighbourhoods such as Anfield and Breckfield. The modest circumstances of these aspiring suburban dwellers called for housing very different in form from the earlier villas. Nearly all the houses that were built in Anfield and Breckfield from the late 1860s onwards were grouped in rows or terraces. The terrace, a quintessentially though not uniquely urban architectural form which rose to prominence in 17th-century London, is highly efficient in its use of space and building materials, yet flexible enough to allow numerous variations in design and scale. Liverpool's earliest terraces dated from the middle of the 18th century and were often formal developments such as the former Clayton Square. But terraces governed by the rigorous enforcement of an overall design were uncommon. More typical even of the early decades of the 19th century were rows of broadly consistent houses, many of which were built to the south-east of the commercial centre, for example in Canning Street (1820s-40s). Elaborate compositions remained rare and some, like the palace-fronted Gambier Terrace (begun early 1830s), were never completed in their intended form.

The modest circumstances of these aspiring suburban dwellers called for housing very different in form from the earlier villas. Nearly all the houses that were built in Anfield and Breckfield from the late 1860s onwards were grouped in rows or terraces. The terrace, a quintessentially though not uniquely urban architectural form which rose to prominence in 17th-century London, is highly efficient in its use of space and building materials, yet flexible enough to allow numerous variations in design and scale. Liverpool's earliest terraces dated from the middle of the 18th century and were often formal developments such as the former Clayton Square. But terraces governed by the rigorous enforcement of an overall design were uncommon. More typical even of the early decades of the 19th century were rows of broadly consistent houses, many of which were built to the south-east of the commercial centre, for example in Canning Street (1820s-40s). Elaborate compositions remained rare and some, like the palace-fronted Gambier Terrace (begun early 1830s), were never completed in their intended form. The earliest terraces to be built in Breckfield were long rows composed of substantial houses of three storeys and basements. Some of these filled up spaces in the uncompleted development of St Domingo Vale, where their building line is thrust well forward of the earlier villas and the narrow front and rear gardens contrast sharply with the more spacious villa grounds. At 60-94 St Domingo Vale the occupants in 1870 included a ship broker, a coal proprietor, several accountants and master mariners, two bookkeepers and a commercial traveller - a mixture of lesser merchants and professional people, prosperous tradespeople and the higher echelons of the salaried white-collar sector (Fig 27).

The earliest terraces to be built in Breckfield were long rows composed of substantial houses of three storeys and basements. Some of these filled up spaces in the uncompleted development of St Domingo Vale, where their building line is thrust well forward of the earlier villas and the narrow front and rear gardens contrast sharply with the more spacious villa grounds. At 60-94 St Domingo Vale the occupants in 1870 included a ship broker, a coal proprietor, several accountants and master mariners, two bookkeepers and a commercial traveller - a mixture of lesser merchants and professional people, prosperous tradespeople and the higher echelons of the salaried white-collar sector (Fig 27).These large, early terraced houses acted as a kind of social buttress to the existing villa communities (Fig 28). The newcomers were, on average, of distinctly lower wealth and status, but their presence ensured that the ' homes of the still less well-off, which proliferated slightly later in the 1870s and 1880s, were built at a discreet and socially supportable distance. Where the villa developments were completed (as at Ash Leigh), nearly so (as at nearby Oakfield, a major development of the 1860s), or were joined by large terraced houses (as at St Domingo Vale), the villas tended to survive for many years, though they inevitably lost some of their exclusivity. Elsewhere isolated villas invariably succumbed sooner or later to the rising tide of mass housing, as owners observed the rising price of land and contrasted it with the dwindling social cachet of the area.

The first large developments of smaller houses had their origins shortly before 1865 when a villa named Breckfield House was demolished and Thirlmere Road was laid out together with a grid of streets linking it to Breck Road. Six of the new streets were named after lakes in the English Lake District, then as now a byword for rural tranquillity. Not unusually, initial progress was slow, and by 1868 only 2 streets out of 11 had been built up, the others following in the early 1870s (Fig 29).

The first large developments of smaller houses had their origins shortly before 1865 when a villa named Breckfield House was demolished and Thirlmere Road was laid out together with a grid of streets linking it to Breck Road. Six of the new streets were named after lakes in the English Lake District, then as now a byword for rural tranquillity. Not unusually, initial progress was slow, and by 1868 only 2 streets out of 11 had been built up, the others following in the early 1870s (Fig 29).

Most of these houses were built in relatively short rows, probably by a number of different builders, but the cumulative result was akin to a series of long terraces. Much of this area has been cleared in recent years, and Thirlmere Road has lost all but a handful of its houses, but a number of streets survive. The houses, uniformly of two storeys though varying in detail, have small forecourts and rear yards. The latter are encroached upon by paired rear ranges known locally as 'outriggers'. In Grasmere Street in 1871 households averaged five people, supplemented by a lodger in about every third house, and resident domestic servants were rare. Heads of household included a bookkeeper, a telegraph clerk, a customs officer, a stonemason, a seamstress, an unmarried woman maintained by her son, and a married woman maintained by her children, one of whom was an architect's assistant, and two of whom were governesses. The lower ranks of 'white-collar' employment predominated.

Most of these houses were built in relatively short rows, probably by a number of different builders, but the cumulative result was akin to a series of long terraces. Much of this area has been cleared in recent years, and Thirlmere Road has lost all but a handful of its houses, but a number of streets survive. The houses, uniformly of two storeys though varying in detail, have small forecourts and rear yards. The latter are encroached upon by paired rear ranges known locally as 'outriggers'. In Grasmere Street in 1871 households averaged five people, supplemented by a lodger in about every third house, and resident domestic servants were rare. Heads of household included a bookkeeper, a telegraph clerk, a customs officer, a stonemason, a seamstress, an unmarried woman maintained by her son, and a married woman maintained by her children, one of whom was an architect's assistant, and two of whom were governesses. The lower ranks of 'white-collar' employment predominated.It is apparent that Liverpool Corporation foresaw that the city's expansion would shortly transform the area and overwhelm the existing network of lanes inherited from its rural past. A number of improvements to the road network were quickly made, not only in the direction of the city centre but to the north as well, where Walton-on-the-Hill was also developing rapidly (Fig 30; see also Fig 25). Around 1865 Breck Road was widened in preparation for a major building campaign. Then in 1868 Oakfield Road was created by widening the former Upper Belmont Road north of its intersection with Breck Road and extending it as far as Walton Breck Road. Robson Street, doubtless named after E R Robson, the Borough Surveyor and architect of Stanley Park, was laid out to a generous width between 1870 and 1873, cutting off a corner between Breckfield Road North and Sleepers Hill, which was itself widened at about the same time. By the early 1870s many more side streets had been laid out between Breckfield Road North and Walton Breck Road, and development between the latter and Anfield Road was already under way. With the exception of Sleepers Hill the improved thoroughfares became the principal commercial streets of the area, profiting from both the residential streets behind them and from passing trade.

The manner in which land was developed for mass housing in the late 19th century can be briefly summarised. Owners of agricultural land or land previously appropriated for villas sometimes acted as their own developers but more often released land for development by others. Of its very nature this process tended to perpetuate existing property boundaries, since only when two adjoining properties were available simultaneously did the opportunity arise to realign or erase a boundary. Whatever the land released, the developer needed to calculate the most desirable way of dividing it up into plots. This was not simply a matter of cramming in the maximum number of houses. A smaller number of more prestigious houses might make a better investment, but only if people of sufficient means could be persuaded to live in them. An assessment of the house type best suited to the social standing of the area was therefore required in addition to the judicious planning of streets, back-alleys and plot boundaries, within the constraints imposed by the lie of the land and the building by-laws, so as to maximise the number of houses of the chosen quality for rent or sale. An owner might also impose conditions, or covenants, on the development, for example to preserve the character of an area close to his own residence. Sometimes an owner might veer in the opposite direction if he wished to provide workers' housing to support a nearby factory or business, though in Anfield and Breckfield, where industries never developed on any scale, this consideration scarcely applied. Whatever the circumstances, these calculations had a profound impact on the way in which the landscape developed.

The manner in which land was developed for mass housing in the late 19th century can be briefly summarised. Owners of agricultural land or land previously appropriated for villas sometimes acted as their own developers but more often released land for development by others. Of its very nature this process tended to perpetuate existing property boundaries, since only when two adjoining properties were available simultaneously did the opportunity arise to realign or erase a boundary. Whatever the land released, the developer needed to calculate the most desirable way of dividing it up into plots. This was not simply a matter of cramming in the maximum number of houses. A smaller number of more prestigious houses might make a better investment, but only if people of sufficient means could be persuaded to live in them. An assessment of the house type best suited to the social standing of the area was therefore required in addition to the judicious planning of streets, back-alleys and plot boundaries, within the constraints imposed by the lie of the land and the building by-laws, so as to maximise the number of houses of the chosen quality for rent or sale. An owner might also impose conditions, or covenants, on the development, for example to preserve the character of an area close to his own residence. Sometimes an owner might veer in the opposite direction if he wished to provide workers' housing to support a nearby factory or business, though in Anfield and Breckfield, where industries never developed on any scale, this consideration scarcely applied. Whatever the circumstances, these calculations had a profound impact on the way in which the landscape developed. Where relatively high housing densities were required, the normal practice in urban and suburban housing developments throughout the 18th and 19th centuries was to create a rectangular grid of streets, yielding the 'rational' benefits of order, regularity and efficient use of space. Much depended on the shape of the available parcels of land, however, and whether these became available for development piecemeal or could be assembled into larger blocks. In essentially rectangular parcels any minor irregularities could be accommodated unobtrusively by varying the size of gardens or yards, but more pronounced irregularities might prove troublesome.

Where relatively high housing densities were required, the normal practice in urban and suburban housing developments throughout the 18th and 19th centuries was to create a rectangular grid of streets, yielding the 'rational' benefits of order, regularity and efficient use of space. Much depended on the shape of the available parcels of land, however, and whether these became available for development piecemeal or could be assembled into larger blocks. In essentially rectangular parcels any minor irregularities could be accommodated unobtrusively by varying the size of gardens or yards, but more pronounced irregularities might prove troublesome.

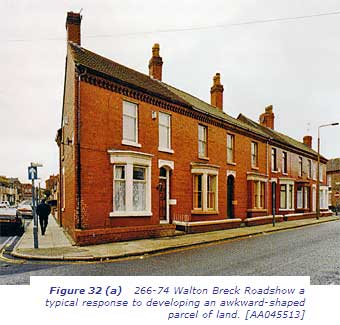

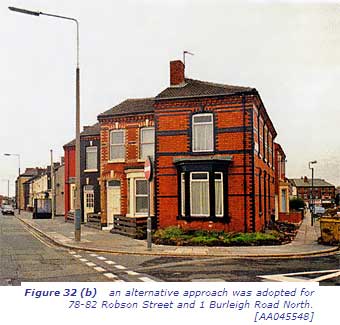

Peculiar problems occurred at those corners of parcels which did not approximate to a right-angle, especially where the market called for high-density housing (Fig 31). Here not only the plots, but often the houses as well, adopt irregular rhomboid plans, and occasionally this expedient is extended along a whole row. A particularly striking example can be seen at 266-74 Walton Breck Road, where the houses, built in the 1890s, have sharply raking gable and party walls, and rooms that must always have been a trial to furnish (Fig 32a).The walls respect the trend of the former field on which they are built, which intersects Walton Breck Road at a pronounced angle. Nos 78-82 Robson Street and 1 Burleigh Road North, a row dating from the late 1870s, illustrate a less common approach to the same problem (Fig 32b). Where the newly created Robson Street sliced through the middle of Burleigh Road North, which had been conventionally laid out in relation to earlier field boundaries less than 10 years previously, the ensuing houses were arranged en echelon to give a staggered series of house fronts. These houses retain a rectangular ground plan, resulting in rooms which are much easier to furnish neatly, but at the expense of an outlook which is shadowed on one side by the blind wall of the next house. Awkward parcels were often among the last to be built upon, as happened with the tapering field now covered by Sockbridge Street and Handfield Street, not built until the late 1880s (Fig 33, below).

Peculiar problems occurred at those corners of parcels which did not approximate to a right-angle, especially where the market called for high-density housing (Fig 31). Here not only the plots, but often the houses as well, adopt irregular rhomboid plans, and occasionally this expedient is extended along a whole row. A particularly striking example can be seen at 266-74 Walton Breck Road, where the houses, built in the 1890s, have sharply raking gable and party walls, and rooms that must always have been a trial to furnish (Fig 32a).The walls respect the trend of the former field on which they are built, which intersects Walton Breck Road at a pronounced angle. Nos 78-82 Robson Street and 1 Burleigh Road North, a row dating from the late 1870s, illustrate a less common approach to the same problem (Fig 32b). Where the newly created Robson Street sliced through the middle of Burleigh Road North, which had been conventionally laid out in relation to earlier field boundaries less than 10 years previously, the ensuing houses were arranged en echelon to give a staggered series of house fronts. These houses retain a rectangular ground plan, resulting in rooms which are much easier to furnish neatly, but at the expense of an outlook which is shadowed on one side by the blind wall of the next house. Awkward parcels were often among the last to be built upon, as happened with the tapering field now covered by Sockbridge Street and Handfield Street, not built until the late 1880s (Fig 33, below).

The terraced houses built in Anfield and Breckfield between the late 1860s and about 1900 vary considerably in size, form, architectural style and detailing. These differences reflect the relative status of different parts of the locality at different periods, and hence the kind of occupants a developer could hope to attract, and the features, both functional and decorative, thought necessary to do so.

The terraced houses built in Anfield and Breckfield between the late 1860s and about 1900 vary considerably in size, form, architectural style and detailing. These differences reflect the relative status of different parts of the locality at different periods, and hence the kind of occupants a developer could hope to attract, and the features, both functional and decorative, thought necessary to do so.The largest houses, on 3 floors and a basement (see Fig 27), might contain 12 main rooms and enjoy perhaps 4 times the floor area of the smallest, which had just 4 rooms arranged on 2 floors.

But even the smallest houses had some pretensions. The most basic house type was built right up to the street and had a door opening directly into the front room, usually doubling as a kitchen and living room with a scullery to the rear.

Even in these houses there was always some decorative brick patterning or eaves decoration on the front elevation and contrary to widespread practice elsewhere in England, where a single window sufficed for the front ground-floor room, there was invariably a window of two sashed lights separated by a turned wooden or plain brick mullion (Fig 34). Details such as these mark out even the smallest houses as a cut above the most basic by-law housing.

Superior houses were distinguished in a variety of ways - and contemporaries would have been alert to the clues. A wider frontage allowed a passage to be run past the front room, which was therefore better suited for use as a parlour, the kitchen-living room being relegated to the rear.

Superior houses were distinguished in a variety of ways - and contemporaries would have been alert to the clues. A wider frontage allowed a passage to be run past the front room, which was therefore better suited for use as a parlour, the kitchen-living room being relegated to the rear.

By setting the house-front behind a small walled and railed forecourt, enough space was left for a bay window to project, dignifying the parlour and affording it a degree of privacy (Fig 35). On the first floor, where the front bedroom extended over both parlour and passage, the greater width of the frontage might be signalled by a pair of windows unless a two-storey bay window, as on many of the houses built in Granton Road in the early 1880s, was preferred (see Fig 39). Most bay-fronted houses had accommodation projecting to the rear as well, in the form of paired 'outriggers' or rear ranges (Fig 36). These vary in what they accommodate: most house water closets or bathrooms and some are large enough to include a scullery and one or more bedrooms.

By setting the house-front behind a small walled and railed forecourt, enough space was left for a bay window to project, dignifying the parlour and affording it a degree of privacy (Fig 35). On the first floor, where the front bedroom extended over both parlour and passage, the greater width of the frontage might be signalled by a pair of windows unless a two-storey bay window, as on many of the houses built in Granton Road in the early 1880s, was preferred (see Fig 39). Most bay-fronted houses had accommodation projecting to the rear as well, in the form of paired 'outriggers' or rear ranges (Fig 36). These vary in what they accommodate: most house water closets or bathrooms and some are large enough to include a scullery and one or more bedrooms. Where shallow plots limited the space for outriggers houses might adopt a double-fronted plan, with a central entrance flanked by bay windows, as at 250, 252 and 254 Anfield Road, built in the 1890s (Fig 37). Alternatively they retained a narrow plan footprint and found extra space in an additional full storey or attic (Fig 38).

Where shallow plots limited the space for outriggers houses might adopt a double-fronted plan, with a central entrance flanked by bay windows, as at 250, 252 and 254 Anfield Road, built in the 1890s (Fig 37). Alternatively they retained a narrow plan footprint and found extra space in an additional full storey or attic (Fig 38).Another decision confronting a prospective builder concerned building materials, which could accentuate distinctions based on plan and morphology. Anfield, Breckfield and the surrounding area yield an attractive red sandstone, but this was used very sparingly on local houses in all but a handful of cases. Instead the terraced houses were built predominantly of brick, much of it thought to have come from brickworks in north-east Wales. The dour brown brick which was used for ordinary work was considerably diversified by the use of polychrome chequer-work, diapers, bands and string courses in red, blue, buff and white and, from the 1880s, moulded terracotta ornament (Figs 39 and 40). Extensive use of the lighter, more even-toned red and buff bricks was restricted to superior buildings.

North Wales was also the source of the slate which became the ubiquitous roofing material of 19th-century Liverpool, and the brisk trade that resulted acted as a conduit both for Welsh migration to Liverpool and for the infiltration of the Liverpool building trade, in which the Welsh established a powerful presence. They included the Venmore family of builders and estate agents, commemorated in Breckfield's Venmore Street. The Welsh influence is reflected in a number of other street names: Dinorwic Road takes its name from one of the largest Welsh slate quarries, Valley Road is probably named after Valley in Anglesey, and Vyrnwy Street possibly recalls the River Vyrnwy, but is more likely to be named after the Lake Vyrnwy Reservoir, created during the 1880s to supply Liverpool's burgeoning population with water.

North Wales was also the source of the slate which became the ubiquitous roofing material of 19th-century Liverpool, and the brisk trade that resulted acted as a conduit both for Welsh migration to Liverpool and for the infiltration of the Liverpool building trade, in which the Welsh established a powerful presence. They included the Venmore family of builders and estate agents, commemorated in Breckfield's Venmore Street. The Welsh influence is reflected in a number of other street names: Dinorwic Road takes its name from one of the largest Welsh slate quarries, Valley Road is probably named after Valley in Anglesey, and Vyrnwy Street possibly recalls the River Vyrnwy, but is more likely to be named after the Lake Vyrnwy Reservoir, created during the 1880s to supply Liverpool's burgeoning population with water. House building in Anfield and Breckfield continued apace into the early 1890s. Liverpool as a whole suffered a slump in the mid-1890s and though recovery speedily followed, and building continued vigorously through most of the first decade of the 20th century, Anfield and Breckfield were by then almost entirely built up and the builders moved on. Some of the last plots to be developed were along the main thoroughfares where they may have been held back while their value rose. A few small parcels and plots, overlooked or withheld in earlier phases of development, were infilled (they can sometimes be identified by anomalies in street numbering) but in most respects the character of the area had already been formed.

House building in Anfield and Breckfield continued apace into the early 1890s. Liverpool as a whole suffered a slump in the mid-1890s and though recovery speedily followed, and building continued vigorously through most of the first decade of the 20th century, Anfield and Breckfield were by then almost entirely built up and the builders moved on. Some of the last plots to be developed were along the main thoroughfares where they may have been held back while their value rose. A few small parcels and plots, overlooked or withheld in earlier phases of development, were infilled (they can sometimes be identified by anomalies in street numbering) but in most respects the character of the area had already been formed. What we see in Anfield and Breckfield today is the achieved form of a landscape which was shaped over many decades, most dramatically in the 30 years between 1865 and 1895. The experience of someone moving to Anfield or Breckfield in the 1870s would have been altogether different from our own. We see streets fully built up in regimented rows, and conclude all too easily that they were the product of a stable, orderly society. The original occupiers, the vast majority of whom were tenants rather than owner-occupiers, and could therefore move from house to house much more freely, would have known how fluid this society really was.

What we see in Anfield and Breckfield today is the achieved form of a landscape which was shaped over many decades, most dramatically in the 30 years between 1865 and 1895. The experience of someone moving to Anfield or Breckfield in the 1870s would have been altogether different from our own. We see streets fully built up in regimented rows, and conclude all too easily that they were the product of a stable, orderly society. The original occupiers, the vast majority of whom were tenants rather than owner-occupiers, and could therefore move from house to house much more freely, would have known how fluid this society really was. Contemporaries would also have seen streets newly laid out on what months before was pasture, and streets which languished in a half-built state while a builder attempted to ride out an economic down turn. The consistent elevations of the houses in Wylva Road, Arkles Road, Edith Road, Miriam Road, Elsie Road and the corresponding length of Walton Breck Road, for example, obscure the protracted evolution of a scheme (including the demolished Kemlyn Road) that was 10 years or more in the making. The first houses were occupied by 1881 but some, including those on Walton Breck Road, were not completed until after 1890. By the time the terraces were going up the earlier villas would have mellowed and their landscaped grounds matured appreciably, so that the contrast with the raw brick terraces, their crisp, mass-produced brick or terracotta ornament and their freshly dug gardens or arid yards would have been for a while as pronounced as the differences in architectural form, scale and setting (Fig 41). Terraces that began with extensive views might see them shut out only months later by another wave of building, while others would overlook small, awkwardly shaped parcels of land for many years - until all the more attractive building plots had been taken up and builders deigned to tackle what was left. It was a landscape both of considerable diversity, and of rapid, sometimes brutal change prolonged over a generation or more. As a writer for The Porcupine, observing the changes at the lower end of Anfield Road, noted bitterly in 1878:

Contemporaries would also have seen streets newly laid out on what months before was pasture, and streets which languished in a half-built state while a builder attempted to ride out an economic down turn. The consistent elevations of the houses in Wylva Road, Arkles Road, Edith Road, Miriam Road, Elsie Road and the corresponding length of Walton Breck Road, for example, obscure the protracted evolution of a scheme (including the demolished Kemlyn Road) that was 10 years or more in the making. The first houses were occupied by 1881 but some, including those on Walton Breck Road, were not completed until after 1890. By the time the terraces were going up the earlier villas would have mellowed and their landscaped grounds matured appreciably, so that the contrast with the raw brick terraces, their crisp, mass-produced brick or terracotta ornament and their freshly dug gardens or arid yards would have been for a while as pronounced as the differences in architectural form, scale and setting (Fig 41). Terraces that began with extensive views might see them shut out only months later by another wave of building, while others would overlook small, awkwardly shaped parcels of land for many years - until all the more attractive building plots had been taken up and builders deigned to tackle what was left. It was a landscape both of considerable diversity, and of rapid, sometimes brutal change prolonged over a generation or more. As a writer for The Porcupine, observing the changes at the lower end of Anfield Road, noted bitterly in 1878:Old-fashioned houses are being dismantled; the rafters show through the unslated roofs; beams and spars stick out like parts of a huge skeleton, and the ragged framework of laths from which the plaster has been stripped seems like a torn bunch of sinews wrenched in pain from the anatomy of the place. And in the stead of these, old hulks stranded in the midst of the advancing desert of town buildings, is springing up the rapid growth of mushroom tenements, each like its fellow, all clean and new, smelling of paint and plaster, marshalled in rows like an army of soldiers; each rank held in command by the towering sergeant who occupies every corner in the shape of the omnipresent 'corner public house in a genteel and rising neighbourhood; certain in a few years to pay well in the midst of a dense population'.

The novelist and social thinker H G Wells spoke for many when he lamented in 1905 'that multitudinous, hasty building for the extravagant swarm of new births that was the essential disaster of the nineteenth century'. History has judged the impact of this phenomenon more kindly. Between the 1840s and 1914 by-law housing transformed huge areas of land on the fringes of England's towns and cities. There were losses, both environmental and emotional, in this process. But over a sustained period the result, undeniably, was a permanent improvement in the average standard of housing for ordinary town-dwellers. The new suburbs were better built, healthier and more spacious than the cellars, courts and back-to-backs of the congested town centres, and they demonstrated that the monster growth in the urban populace could be housed decently.

The novelist and social thinker H G Wells spoke for many when he lamented in 1905 'that multitudinous, hasty building for the extravagant swarm of new births that was the essential disaster of the nineteenth century'. History has judged the impact of this phenomenon more kindly. Between the 1840s and 1914 by-law housing transformed huge areas of land on the fringes of England's towns and cities. There were losses, both environmental and emotional, in this process. But over a sustained period the result, undeniably, was a permanent improvement in the average standard of housing for ordinary town-dwellers. The new suburbs were better built, healthier and more spacious than the cellars, courts and back-to-backs of the congested town centres, and they demonstrated that the monster growth in the urban populace could be housed decently. For thousands, single-family occupancy of a house enjoying its own sanitation and a constant water supply - even if that meant a single tap in the kitchen or scullery - became an achievable goal. It is true that the houses mostly remained the property of landlords, who might raise rents or neglect repairs as arbitrarily as before, and that many of the people who took the new houses lived lives which we - and perhaps they - would have considered pinched and thwarted. It is equally true that for decades much poor-quality earlier housing elsewhere continued in use, for many could not afford the rents which the new houses commanded and some were reluctant to sunder bonds of kinship and association cemented by the older, cheek-by-jowl pattern of urban life. But the slum-dwellers of the late 19th century occupied an increasingly marginal space in society. The popular unrest which had periodically threatened the social and political establishment before 1850 diminished sharply as the century progressed, and while many reasons for this change can be advanced, including generally rising national prosperity and progressive electoral reform, it is likely that the spread of by-law housing played a not insignificant part in allaying discontent. Standards of order and decency had been set which in later decades, through slum clearance and public housing programmes, would come within reach of all sections of the population.

For thousands, single-family occupancy of a house enjoying its own sanitation and a constant water supply - even if that meant a single tap in the kitchen or scullery - became an achievable goal. It is true that the houses mostly remained the property of landlords, who might raise rents or neglect repairs as arbitrarily as before, and that many of the people who took the new houses lived lives which we - and perhaps they - would have considered pinched and thwarted. It is equally true that for decades much poor-quality earlier housing elsewhere continued in use, for many could not afford the rents which the new houses commanded and some were reluctant to sunder bonds of kinship and association cemented by the older, cheek-by-jowl pattern of urban life. But the slum-dwellers of the late 19th century occupied an increasingly marginal space in society. The popular unrest which had periodically threatened the social and political establishment before 1850 diminished sharply as the century progressed, and while many reasons for this change can be advanced, including generally rising national prosperity and progressive electoral reform, it is likely that the spread of by-law housing played a not insignificant part in allaying discontent. Standards of order and decency had been set which in later decades, through slum clearance and public housing programmes, would come within reach of all sections of the population.

« Previous Top Home Next »