The development of Liverpool

Figure 1 (right) The Liverpool waterfront today,with the 'Three Graces': The Royal Liver Building (1908-10) to the left, the Cunard Shipping Company Offices (1914-16) in the centre, and the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company Offices (1907) to the right.. [AA029230]

Figure 2 The Liverpool waterfront in the age of sail and steam: Samuel Walters, The Port of Liverpool, 1873. {National Museums, Liverpool (The Walker)]

Figure 3 Liverpool's trading network: focused on the North Atlantic triangle, it extended to South America and Asia.

Gawthrop 1861, 29

Some of the world's great cities are united in the popular mind with their river, and for reasons both ancient and modern Liverpool and the Mersey arc inseparable (Fig 1). The relationship is not the same as that which we see in cities such as Paris, which develop on both banks of their river and where bridging points concentrate life and traffic on the waterfront. Instead, the great muddy river, too broad to span, runs past rather than through the city. But the Mersey is the reason for Liverpool's existence. Treacherous, fast flowing, with a huge tidal range, it nevertheless formed part of the chain that carried the trade of the world, linking large parts of northern and midland England with markets and sources of supply across the globe. For centuries, this traffic passed through Liverpool, the landing point for imports and the port of dispatch for goods sent overseas or around the coast (Fig 2). By the mid-19th century, Liverpool was far and away the dominant port for exports, handling 45 per cent of the United Kingdom total by value.

Some of the world's great cities are united in the popular mind with their river, and for reasons both ancient and modern Liverpool and the Mersey arc inseparable (Fig 1). The relationship is not the same as that which we see in cities such as Paris, which develop on both banks of their river and where bridging points concentrate life and traffic on the waterfront. Instead, the great muddy river, too broad to span, runs past rather than through the city. But the Mersey is the reason for Liverpool's existence. Treacherous, fast flowing, with a huge tidal range, it nevertheless formed part of the chain that carried the trade of the world, linking large parts of northern and midland England with markets and sources of supply across the globe. For centuries, this traffic passed through Liverpool, the landing point for imports and the port of dispatch for goods sent overseas or around the coast (Fig 2). By the mid-19th century, Liverpool was far and away the dominant port for exports, handling 45 per cent of the United Kingdom total by value. Most major ports and towns had large numbers of warehouses, serving both inland and overseas trade and the everyday requirements of local or regional markets. Some towns display impressive collections of warehouses: Gloucester has huge buildings, clustered around its canal basin, that were constructed to store iron and grain; and in Manchester there developed a particular type of warehouse - the cotton packing and shipping warehouse - to serve the region's principal manufacturing industry. Liverpool is different to these and all other English towns. Unlike Bristol and Hull, it had an undistinguished role in national history before the 18th century; unlike Manchester, it did not develop a large industrial economy. Liverpool developed to serve a growing national and international trading network and for many decades handled more of the cargoes of Great Britain's maritime empire even than London. Here, therefore, the warehouse represents the essential function of the city and nowhere else can the evolution of this important building type be studied in such depth from surviving buildings.

Most major ports and towns had large numbers of warehouses, serving both inland and overseas trade and the everyday requirements of local or regional markets. Some towns display impressive collections of warehouses: Gloucester has huge buildings, clustered around its canal basin, that were constructed to store iron and grain; and in Manchester there developed a particular type of warehouse - the cotton packing and shipping warehouse - to serve the region's principal manufacturing industry. Liverpool is different to these and all other English towns. Unlike Bristol and Hull, it had an undistinguished role in national history before the 18th century; unlike Manchester, it did not develop a large industrial economy. Liverpool developed to serve a growing national and international trading network and for many decades handled more of the cargoes of Great Britain's maritime empire even than London. Here, therefore, the warehouse represents the essential function of the city and nowhere else can the evolution of this important building type be studied in such depth from surviving buildings. Liverpool's rise from a fishing village to a port of global importance began in the Middle Ages, based on trade with Ireland and Scotland. By the 16th century, links had been established with the Atlantic ports of continental Europe in France, Spain and Portugal, and trade with North America began in the mid-17th century. Activity was, by later standards, modest: in 1700 just over 100 vessels entered the port. Horizons broadened in the 18th century, when the Atlantic triangle was developed, sending English manufactured goods and trinkets to Africa, slaves from there to plantations in the Caribbean and North America, and, last, rum, sugar and cotton back to England.

Liverpool's rise from a fishing village to a port of global importance began in the Middle Ages, based on trade with Ireland and Scotland. By the 16th century, links had been established with the Atlantic ports of continental Europe in France, Spain and Portugal, and trade with North America began in the mid-17th century. Activity was, by later standards, modest: in 1700 just over 100 vessels entered the port. Horizons broadened in the 18th century, when the Atlantic triangle was developed, sending English manufactured goods and trinkets to Africa, slaves from there to plantations in the Caribbean and North America, and, last, rum, sugar and cotton back to England.At first, Bristol disputed supremacy in the Atlantic trade, but by the early 19th century Liverpool's status as the port for a rapidly developing industrial hinterland made it pre-eminent: in 1800 more than 4,000 vessels arrived here. The abolition of the slave trade in 1807 did little damage to the city's economy, for traffic grew with the addition of India, China and South America to Liverpool's network of trading links, and by 1871 more than 19,000 ships used the port (Fig 3).

In a period when most people's horizons were very limited, the bustling activity of the docks and the sometimes-exotic links indicated by the nature of the goods in transit were the subject of wonder. They also demonstrated how mercantile enterprise was the foundation of the city's wealth (Fig 4).

Figure 4 St Nicholas's Church, George's Dock Basin and the warehouses on New Quay. This photograph of c 1880 gives some impression of the everyday scene on the quayside: a forest of masts can be seen in Prince's Dock to the left. [Local Illustrations Collection 326, Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]

The port's growing trade was assisted by the development of a sophisticated system of port and transport facilities, many promoted by the town's Corporation and leading merchants. Early in the 18th century, to overcome the poor mooring facilities on the river and in the tidal inlet, known as the 'Pool', the Corporation ordered the construction of an enclosed wet dock. This, the first purpose-built commercial wet dock in the world, was built by Thomas Steers and opened in 1715. Later adapted to form part of the growing dock system, and then filled in and built over, the walls of the dock survive in part below ground. Tiny by later standards, the dock was, nevertheless, a significant investment for the Corporation, seeking to encourage merchants to use the port. Over the next century, the docks grew until, by 1810, they could be described as 'the most indubitable memorials of mercantile enterprize and transcendent utility' (Troughton 1810, 271).

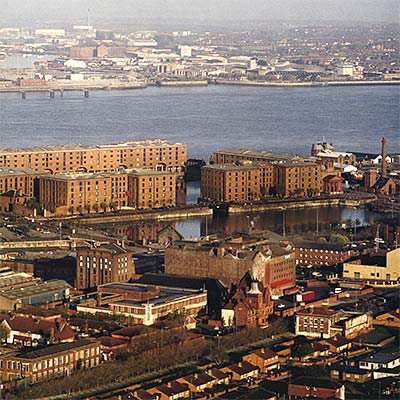

Later growth was even more spectacular, and ultimately the docks occupied an 11-kilometre frontage to the river. The greatest name associated with this huge endeavour is Jesse Hartley, Dock Engineer from 1824 to 1860, for it was he who designed and engineered the most notable facilities, those at Albert, Stanley and Wapping Docks, with their heroically scaled warehouses (Fig 5).

Figure 5 The Albert Dock and its warehouses, the work of Jesse Hartley, opened in 1846. [AA029235]

Liverpool was connected to its hinterland by an important network of waterways (Fig 6). Already in the late 17th century, the Mersey was made navigable as far upstream as Warrington, and, before the age of the railways, the Douglas, Weaver and Irwell rivers were improved to take water transport, and the Sankey, Bridgewater and Leeds & Liverpool canals were opened. In 1810 it was said that Liverpool's 'contiguity to navigable rivers; namely the Dee, the Weaver, and the Irwell; the numerous canals; and its spacious docks, so conveniently arranged for communication with each other and the river; its vicinity to Manchester, and its facility of intercourse with Birmingham and other distant manufacturing towns' made it the natural focus of trading activity for the manufacturing regions of the west midlands, Lancashire and Yorkshire (Troughton 1810, 101).

The opening in 1830 of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, at first successful mainly in carrying passengers, ushered in the railway age and with it the prospect of speedier bulk transport throughout a national network. The city's crucial role as a destination for imports and exports was seriously threatened only in 1894, when the opening of the Manchester Ship Canal offered the inland industrial region the option of bypassing the port that for more than a century had served its trading activities.

The immense volume of trade that passed through Liverpool transformed the town, turning it from little more than a village into England's second city. Its population rose from 5,000 in 1700 to 25,000 in 1760, to 77,000 in 1800 and to 311,000 in 1841, and the built-up area swallowed formerly outlying villages such as Everton and Walton.

The character of the city was decidedly commercial: the Town Hall of 1749-54 provided an Exchange for merchants on its ground floor; banks, chambers, shipping companies and insurance houses proliferated to service the trading activities of the port; and the Custom House, rebuilt many times, presided over the collection of excise.

The great wealth accumulated in the course of business found architectural expression in a wide range of buildings for the affluent merchants and the business community: the substantial houses of the extensive Georgian and Victorian suburbs, the clubs and the cultural and professional institutions demonstrate that Liverpool's elite lived in fine style.

Figure 6 Liverpool and its region, showing the pre-1850 navigation systems,

which linked the port with a vast manufacturing and agricultural hinterland.

The everyday aspects of trading life were very evident in the town and gave it a distinctive character, much remarked upon by commentators (Fig 7): in 1820, for example, it was observed (Anon 1820, 188-9) that

The Old Dock, running eastwards into the town, presents the interesting spectacle of a number of ships, which, two centuries ago, would have been thought a complete navy, floating, in perfect security, in the very heart of a large town, mingling their lofty masts in the perspective of houses, churches, and other public buildings, and immediately surrounded with shops ... victualling and drinking houses, and stores and erections for every mechanical operation connected with the naval department.

Figure 7 'View of the Harbour of Leverpool', E Rooker, 1770.

[Local Illustrations Collection 294, Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]

[Local Illustrations Collection 294, Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries]

Inland from the later docks, industries and warehousing developed alongside housing for the labouring classes. The transformation brought to the area was remarked upon in the late 19th century by J A Picton (1875, II, 43), Liverpool's chronicler of the period, who wrote of the formerly genteel area of Love Lane that:

The opening of the canal changed entirely the whole aspect of affairs. The zephyrs became redolent of coal-dust. Merchandise and traffic, with their sordid requirements, soon absorbed the pleasant nooks and corners. Fashion and comfort took their flight to more congenial regions, and the neighbourhood was left to the bustle of active industry

...Love Lane is still a shady avenue, but it is with shadows of huge piles of warehouses and the viaduct of the railway.

Picton (an architect rather than an engineer, and one who even considered the Albert Dock 'a hideous pile of naked brickwork' and an 'incarnation of ugliness') introduces the warehouse to this story (1875,1, 570). Liverpool's growth from a port of modest size in the early 18th century to the hub of an imperial trading network in the early 20th is strikingly represented in the development of this building type.

« Pictures Top Home Next »