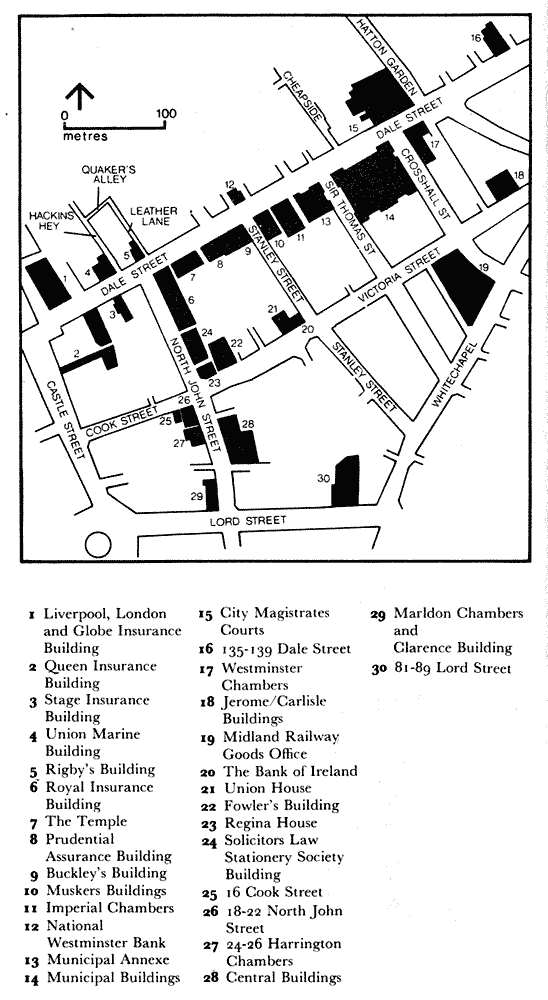

The second city centre walk starts in High Street, at the junction of Castle Street and Dale Street. High Street previously ran through to Old Hall Street and was the main street of the town. Dale Street was then the principal route into the town from Manchester and London, and was a very busy and populous thoroughfare. At the east end of the street was a bridge over the brook which ran along the line of Byrom Street and Whitechapel into the Pool. The street was first widened in 1786 and buildings were erected on the north side corresponding with the stucco terraces of Castle Street. Since it was the main entry to and from the town, inns and taverns were numerous, but gradually during the nineteenth century these were replaced by a series of large and impressive commercial premises: One of the first of these was the Liverpool and London and Globe Insurance Building erected in 1855-7 and designed by C. R. Cockerell, architect of the nearby Bank of England. It is a fine classical building of seven bays with attached columns on the second floor and an imposing, very original doorway set in a French niche of banded rustication. Also original is the diagonal treatment of the staircases on the High Street facade. The mansard roof and dormer windows are later additions which mar the original proportions.

The second city centre walk starts in High Street, at the junction of Castle Street and Dale Street. High Street previously ran through to Old Hall Street and was the main street of the town. Dale Street was then the principal route into the town from Manchester and London, and was a very busy and populous thoroughfare. At the east end of the street was a bridge over the brook which ran along the line of Byrom Street and Whitechapel into the Pool. The street was first widened in 1786 and buildings were erected on the north side corresponding with the stucco terraces of Castle Street. Since it was the main entry to and from the town, inns and taverns were numerous, but gradually during the nineteenth century these were replaced by a series of large and impressive commercial premises: One of the first of these was the Liverpool and London and Globe Insurance Building erected in 1855-7 and designed by C. R. Cockerell, architect of the nearby Bank of England. It is a fine classical building of seven bays with attached columns on the second floor and an imposing, very original doorway set in a French niche of banded rustication. Also original is the diagonal treatment of the staircases on the High Street facade. The mansard roof and dormer windows are later additions which mar the original proportions.On the other side of Dale Street is the Queen Insurance Building designed by Samuel Rowland for the Royal Bank and built in 1839. It has a grand facade with giant upper Doric and Ionic columns and a big top balustrade supporting the coat of arms of the Royal Bank. Segmental arches surmounted by ornamental iron screens lead to Sweeting Street and Queen Avenue, at the end of which is an elegant and finely proportioned building by the same architect. Inside is a large hall with a marvellous rich classical plaster ceiling. Next in Dale Street is the State Insurance Building, half of the front of which has been demolished. This is another original building by Aubrey Thomas, architect of the Royal Liver Building, and was built in 1906. The design shows a very free treatment of Gothic forms which in their flowing lines are almost Art Nouveau. Behind this facade the offices are placed around a galleried court with a glass tunnel vault. The Union Marine Buildings opposite is a typically robust design by Sir James Picton. The ground floor has large round-arched windows with keystones and marble panels between, and at the top is a very heavy projecting cornice with rope moulding on round arched machicolations. Across Hackins Hey is Rigby's Buildings a Victorian stuccoed building with rich decoration. Although the facade carries the date of 1726, the present building is probably not earlier than 1850. The second floor is the most elaborate with small balconies and pediments, and at the top is a balustraded parapet with urns and actoreria and the inscription 'Rigby's Buildings'.

The small alleyways behind Rigby's Buildings including Hackins Hey, Quaker Alley and Leather Lane are worth examining, for although they contain no listed buildings they give an indication of the character of Liverpool before the main streets were widened.

Opposite this area, on the corner of Dale Street and North John Street, is another of the early twentieth century giant office blocks The Royal Insurance Building erected in 1897-1903. The architect, J. Francis Doyle, was chosen from a limited design competition with seven entrants, the assessor Norman Shaw being retained as advisory architect. Doyle, who had worked with Shaw on the White Star Building, was so heavily influenced by Shaw's style that he was able to refashion it, the gable being taken straight from the earlier building. It is however, an extremely impressive building; the granite and Portland stone exterior conceals a steel frame of advanced design giving a column-free general office occupying most of the ground floor. The sculptured frieze a typical Arts and Crafts motif by C. J. Allen, takes as its theme insurance in its various forms, and runs around three sides of the building. The campanile with an octagonal cupola, gilded dome and sundial forms a prominent feature in the.City skyline. The adjacent building in Dale Street is The Temple, designed by J. A. Picton and Son for Sir William Brown and erected in 1864-5. It is in an Italianate style with a central turret forming a large rusticated round arch on the ground floor leading to an open arcade.

Facing the end of Moorfields is the Prudential Assurance Building by Alfred Waterhouse and built in 1885-6 (the tower was added in 1906) in his typical harsh red terracotta and brick late Gothic style. The decoration is much simplified, relying mainly on scale and rhythm for effect, but the corner treatment with its oriel window and twin gable shows Waterhouse's compositional skill. The adjoining Buckley's Buildings is included in the listing for its group value. It is also of brick, but with stone dressings and turns the corner into Stanley Street.

Then Muskers Buildings, formerly the Junior Reform Club, is more conventionally Gothic, with large pointed arched windows with cusped tracery. The neighbouring Imperial Chambers is also Victorian Gothic. The central office entrance with composite columns leads to a glass roofed hall crossed by iron bridges.

Opposite the end of Stanley Street is the National Westminster Bank a stuccoed three storey Victorian Building with a banded rusticated ground floor supporting pilasters and giant fluted columns with elaborate Corinthian capitals. Further east is the Municipal Annexe built in 1883 as the exclusive Conservative Club and designed by F. and G. Holme. It is in a bold French Renaissance style with an iron balcony on the first floor and symmetrical wings topped by high truncated roofs with pedimented windows. Municipal Buildings was built in 1860-6 to the designs of the Corporation Surveyor, John Weightman, and completed by his successor, E. R. Robson. This large building is in a mixture of Italian and French Renaissance styles with symmetrical French pavilion roofs, in the centre of which is a tower with a curious freely shaped spire or steep pyramid roof. This has a wrought-iron balcony half way down which was described by C. H. Reilly as 'like a skirt popped over the head (if that is ever done) and not allowed to settle into its proper place.' The giant Corinthian columns and pilasters have different designs to all the capitals, which is a Gothic rather than Renaissance conception, and the building is further adorned by its sixteen fine sculptured figures.

The City Magistrates Courts on the north side of Dale Street were built in 1857-9 and also designed by Weightman. This is a signified three storey ashlar building with a central pediment and carriage entrance below. Around the corner in Hatton Garden, the Fire Station is by Thomas Shelmerdine, Corporation Surveyor after E. R. Robson. Built in 1898 it is an interesting composition combining Jacobean and Art Nouveau motifs. Then the City Transport Offices, also by Shelmerdine, built in 1905-7 and another good facade, this time with Edwardian Imperial features including architectural sculpture. Behind these buildings, but accessible from Cheapside, is the Main Bridewell designed by John Weightman and built in 1860-4. It is a typically severe neo-classical prison building, the main front being separated by a courtyard from the massive rusticated gate piers at the entrance.

The last buildings of note in Dale Street are Nos. 135-139, a terrace of late eighteenth century brick houses. No. 139 was built for John Houghton, a distiller, whose works were nearby. On the Trueman Street elevation is a Venetian window with some Adam style decoration and a fine tripartite doorway.

On the south side of Dale Street, between Crosshall Street and Preston Street, stands Westminster Chambers built in 1880 in the Gothic style. The Crosshall Street facade has two pointed arched doorways with carved mouldings and granite columns. The adjacent Juvenile Court was formerly a Wesleyan Chapel built in 1878-80 and designed by Picton junior. It is an original building in an early thirteenth century style built of small rusticated stones. Round the corner in Victoria Street, between Crosshall Street and Kingsway, are the matching Jerome Buildings and Carlisle Buildings dated 1883. These have a distinctive roofline with their projecting dormers with three light windows and pagoda like roofs.

Victoria Street is a new street formed in 1867-8 to improve the flow of traffic and produce a new and impressive location for commercial development. The western section of the street followed the line of the existing Temple Court, which accounts for the gentle curved frontage of the Fruit and Produce Exchange Buildings. Probably the most impressive building in Victoria Street is, in fact, not commercial but principally a warehouse, the Midland Railway Goods Offices erected about 1850. A bold and functional design it was built by the Midland Railway for the receipt and dispatch of their goods, the great doorways being sufficiently high to admit the largest load. The main front has a slightly concave face with the windows set in giant round arches with keystones and imposts. The Victoria Street facade has carved spandrels with shields of arms and carved names of Midland Railway Stations.

The General Post Office of 1894-9 was designed by Sir Henry Tanner but had its first floor removed after war damage which accounts for its unfinished appearance. The Bank of Ireland, formerly the Westminster Bank, on the corner of Stanley Street, was built circa 1870. It has an interesting functional facade to Stanley Street with cast iron mullioned windows and tall lift shafts. Adjacent to the Bank of Ireland is Union House built in 1882, a five storey block with polished granite columns to the ground and first floors. The most interesting feature of the building is the cast iron staircases with a wall of stained glass depicting the harvesting and packing of merchandise in foreign lands. It is possible to see this glass at night from the side passage, Progress Place, where it fits within a robust cast iron and glass facade. Fowler's Buildings is an office block built in 1864 to the design of J. A. Picton. It is of stone with eight granite Tuscan columns, round arched windows and a heavy top cornice on brackets. Adjoining this, on the corner of North John Street, is Regina House which includes the Beaconsfield Public House, and then around the corner in North John Street the Solicitors Law Stationery Society Building of 1854. This is a narrow four storey building stuccoed on the upper floors and enriched with balconies, carved lintels, and on the top floor, three round eyes, the centre one decorated as a laurel wreath. An ingenious roof extension has recently been added.

At the bottom of Cook Street is the second and only other recorded building by Peter Ellis, architect of Oriel Chambers. It is No. 16, built two years later than Oriel Chambers in 1866, and is just as original. The front has three giant bays in a Venetian window head filled in with plate glass, but in the courtyard to the rear is the most remarkable feature. Here a surprisingly 'modern' glazed cast iron spiral staircase cantilevered from each floor is squeezed into the corner against a wall of glass with slender iron mullions. In its stripped aesthetic it is far in advance of its time, and Ellis would seem to have paid the penalty by receiving no further architectural commissions. After this date he is recorded only as working as a civil engineer.

The adjacent corner building, Nos. 18-22 North John Street, is a mid-nineteenth century office building with modern shops on the ground floor and upper walls stuccoed. Nos. 24-26 (Harrington Chambers) is similar, but later in date and has giant panelled pilasters and pedimented dormers. Central Buildings opposite is a huge and imposing symmetrical block. The heavily moulded upper floors are seated on a colonnade of red granite Doric columns filled in with plate glass, giving light to the shops behind.

Marldon Chambers and Clarence Building, situated on the corner of North John Street and Lord Street, are an example of the Victorian classical style, being later than the original classical facades of Lord Street by John Foster in the 1820s. The giant fluted composite pilasters and deep frieze and cornice above the second floor windows give the facade a grand scale, and the end three bays are emphasised by a pediment and four half columns instead of pilasters.

The only other building of special note in Lord Street is Nos. 81-89. This is a late nineteenth century block which achieves a striking effect by the use of alternate horizontal bands of white and yellow stone. Three segmental arches frame three upper floors, the middle one recessed to form a reversed bay. Above this are three steep gables containing a series of lancet windows and punctuated by octagonal turrets.

« Previous Top Home Next »