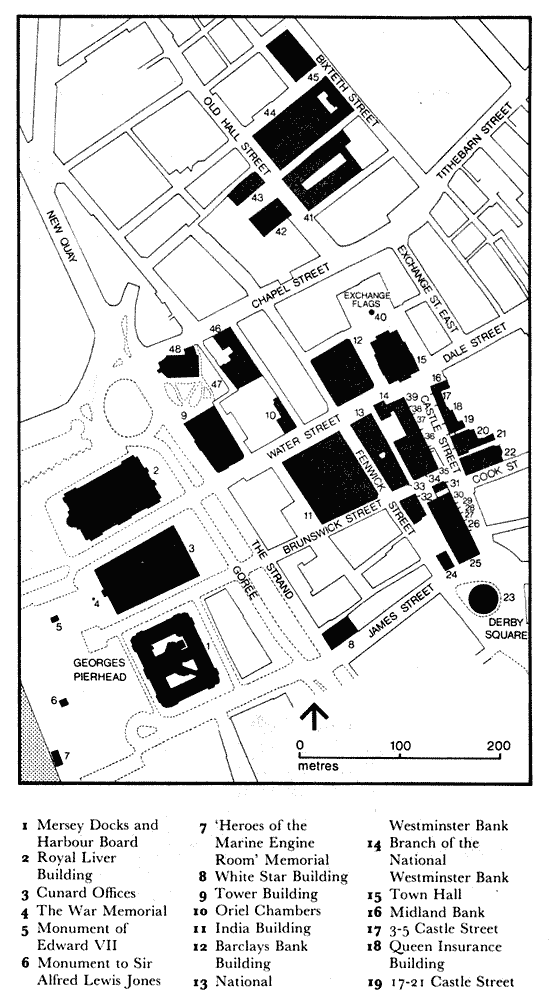

The growth of the docks on which Liverpool's wealth and trade were based was accompanied by the development of commercial premises in the old part of the City. Until the 1820s traders carried out their work from their houses and shops, which were packed together with warehouses in the narrow thoroughfares around the Castle Street, Water Street, Chapel Street and Old Hall Street area.

Gradually, with their expanding wealth and greater social aspirations, the leading merchants moved their households out to more spacious premises in Duke Street and beyond, leaving the old core to take on a more intensley commercial character. Rents and land values soared, and redevelopment was carried out with increasing zeal. Before the mid-nineteenth century, office buildings were not a specific building type of any significance, but the growing power of Victorian commerce gave companies the desire and means to express their prestige and importance by erecting splendid and dignified premises for their business operations. Liverpool's zenith was reached at the turn of the century with the construction of the Pier Head group of office buildings, in spirit profoundly expressive of the Imperial optimism of Edwardian enterprise.

It is these three buildings constructed on the land gained by filling in the George's Dock that give Liverpool her famous skyline, reminiscent of the great North American Cities with which her principal trade was then carried out. The first to be built was the Offices of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board completed in 1907 to the designs of Arnold Thornley. This impressive symmetrical block takes the form of a Renaissance palace with cupolas at its corners and in the centre a large classical church dome on a high drum. Internally an octagonal hall reaches up to the dome with arched galleries running around it at four levels. The Royal Liver Building, erected in 1908- i o, has no counterpart in England and is one of the world's first multi-storey buildings with a reinforced concrete structure. It was designed by Aubrey Thomas in a remarkably free and original style. The sculptural clock towers are surmounted by domes on which the famous mythical Liver Birds are perched. The last of this trio of waterfront buildings is the Cunard Offices designed by Willink and Thicknesse with Arthur Davis (of Mewes and Davis) as consultant, and constructed during the Great War. It is built in the style of an Italian palazzo but with Greek revival details, and it is very nicely proportioned. Less ofa tour deforce than either the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board or the Liver Building, it can nevertheless stand a closer and more critical architectural examination.

The Pier Head also contains a number of monuments of note. The War Memorial, in front of the Cunard Building'takes the form of a granite pedestal crowned by a copper figure of Victory. The Monument of Edward VII by Sir W. Goscombe John was intended by the sculptor to stand on the steps of St. George's Hall. Fortunately, after a vociferous public campaign organised by Sir Charles Reilly, this was prevented and the equestrian statue was dispatched to its present site. The Monument to Sir Alfred Lewis Jones by Sir George Frampton, unveiled in 1913, consists of a square stone pedestal with a bronze figure at the top representing Liverpool and its shipping. The Memorial to the 'Heroes of the marine engine room' also by Goscombe John was paid for by international subscription and erected in 1916. It shows lifesize standing figures of engineers and firemen in high relief, and was originally intended to commemorate those lost in the Titanic disaster of 1912.

On the corner of The Strand and James Street, opposite the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board building, stands the White Star Building erected in 1898 and the first of the new generation of giant office blocks built in the City. It was designed by Norman Shaw with J. Francis Doyle, and, like New Scotland Yard, is striped with bands of brick and white portland stone. Its height is emphasised by angle turrets and tall chimneys which make a striking effect when viewed on approach from the south along the dock road. After serious war damage the main gable to The Strand was rebuilt to a simpler design.

Tower Building on the corner of Water Street was designed by Aubrey Thomas predating his other work, the Royal Liver Building, by two years. It is similarly inventive, and, built in 1908, was one of the earliest steel framed buildings in the country. It lacks any architectural refinements however, the designer being more concerned with functional requirements such as the large windows which admit good light and the use ofself-cleaning white glazed tile as an exterior cladding. Tower Building is so called because it stands on the site of the Tower of Liverpool, a fortified house on the river's edge belonging to the Stanley family, Earls of Derby. This building was used by the Stanleys as an embarkation base for the Isle ofMan and their property in Ireland, but towards the end of the eighteenth century it fell into disrepair and became a gaol for criminals and debtors.

In the eighteenth century Water Street was a fashionable place of residence for the wealthy class of Liverpool merchants: it is now one of the finest of the commercial streets. Oriel Chambers (grade I) designed by the practically unknown Liverpool architect, Peter Ellis, and built in 1864 is one of the most significant buildings of its date in Europe. The Water Street and Covent Garden elevations have tall stone mullions with nail head decoration separating graceful cast iron windows which provide excellent lighting to the offices behind. At the rear, stripped of all decoration, the long projecting bands ofwindows are remarkably prophetic of the twentieth century. The building's functional design aroused a great deal of controversy in its day - it was described as 'a great abortion' and 'an agglomeration of protruding plate glass bubbles.' Today we appreciate its honesty, its elegant detailing and its reflective qualities, and we can admire its revolutionary impact.

Opposite Oriel Chambers is India Buildings designed by Herbert J. Rowse, the most influential Liverpool architect of the inter-war years, as the result of an architectural competition. It was built between 1924 and 1932 at the cost of,EI.25 million for Holt's Blue Funnel Line, and is one of the largest office blocks in the City. Such a huge provision of offices being considered highly speculative at the time, the building was so designed that it could be converted into a warehouse. In its simplified neo-classical style it is typical of American office designs of that time, and Rowse was certainly influenced by his extensive travels in North America. The most notable feature is the barrel vaulted arcade that runs through the centre of the block lined by small shop fronts.

The Barclays Bank Building, originally the headquarters of Martins Bank and completed in 1932, was also a competition success for Rowse. This building is similarly monumental in scale and is American-French classical in origin. It has a steel-framed construction, and the design of servicing which incorporated completely ducted pipes and wires and low temperature ceiling heating was very advanced. The bronze entrance doors in low relief are of note, and having passed through them the Jazz Age Parisian interior with its Egyptian motifs is particularly splendid.

The National Westminster Bank on the corner of Fenwick Street, built in 185o is distinguished by giant fluted Doric columns rising through first and second floors. This monumental treat-ment is given stability by heavy rustication to the ground floor and a plinth of polished red granite. Note the bronze doors with sculptured tigers' heads, and the fine classical interior with ornamented plasterwork and columns.

Adjoining this and also now a branch of the National Westminster Bank is an attractive early Renaissance style building. This is typical of the mid-nineteenth century Liverpool bank buildings with its closely spaced classical windows and heavy cornice.

It was said by Sir James Picton that 'the history of Castle Street is the history of Liverpool' and this fine street still remains the identifiable centre ofthe City. The streets of the town were laid out at the beginning of the thirteenth century, the seven original ones being Dale Street and Water Street, Tithebarn Street and Chapel Street and, running across Old Hall Street, High Street and Castle Street ending at the castle which was built in 1235. After the civil war the castle fell into disuse and was finally demolished in 1721 to make way for St. George's Church, now Derby Square. This area formed the market place which gradually encroached so far along Castle Street that it reached the Town Hall, in front of which the merchants at that time congregated. By the mid-eighteenth century Castle Street had become a street ofshops, and the most fashionable place in town, but when the market was moved, it was abandoned to commerce and was widened to its present generous proportions in 1786.

The existing Town Hall (grade I) is the City's third and was designed by John Wood of Bath and built in 1749-54. It was intended that the ground floor should act as an exchange for the merchants to transact their business, whilst municipal functions would be carried out on the floors above. The building was seriously damaged by fire in 1795 and James Wyatt was commissioned to reconstruct it, which he did adding first the impressive dome on its high drum and later, with John Foster, the two storey Corinthian portico. Wood's work, elegant and finely etched, can best be seen from Exchange Flags, whilst Wyatt's additions give weight and grandeur to the main facade. The interiors were not completed until 182o, but together they form an exceptionally fine example of late Georgian decoration, and one of the best suites of civic rooms in the country. The building has survived numerous attempts at damage. In 1775 seamen protesting against the reduction in their wages attacked it with a cannon, for their employers were sheltering inside, and in 1881 there was an abortive attempt by the Fenians to blow it up. War damage, following a raid in June 1941, was more serious, but since then it has been well restored.

On the corner of Dale Street and Castle Street is the late nineteenth century Midland Bank by Edward Salomons. distinguished architect of the Manchester Reform Club. Built as an art gallery for Thomas Agnew & Co., it is of red brick and has a deep frieze at the top with swags and wreaths. Nos. 3-5 Castle Street were built in 1889 to the design of Grayson and Ould for the British and Foreign Marine Insurance Company whose inscription can be seen on a colourful mosaic frieze over the first floor. Distinctive features are the balustraded balconies and dormer windows with their unusual gables and curved pediments.

Nos. 7-15 are part of the Queen Insurance Buildings whose principal front is on Dale Street. On the ground floor ofthe facade to Castle Street is the access to Queen Avenue, an arcade with walls of glazed brick and oriels with pargetted aprons, accessible through a wide shallow arch decorated with iron spandrels. The side arches are filled in with modern shops and, on the floors above, the brick and dressed stone facade is of great decorative variety and richness.

Nos. 17-21 Castle Street are a typical Victorian commercial building of polished granite and stone. The facade is divided on each floor by pilasters and columns of different orders with friezes and cornices forming bands between floors. No. 25, which extends over the entrance to Sweeting Street, is of similar composition, but with even greater surface decoration. The top floor rises over the three centre bays only and is surmounted by a curved pediment with acroteria.

The Huddersfield Building Society, formerly the Norwich Union building is a little earlier in date than these other buildings, and, although smaller in size, has greater architectural distinction. Its portico of four giant fluted attached Corinthian columns and pediment rests on a heavy stone cornice and parapet with ground floor granite pilasters. It is a valuable neighbour to the famous Bank of England built in 1845-8 which is considered to be C. R. Cockerell's best work. Cockerell's design for the main facade is a free adaptation of Greek motifs on a grand scale giving the building an importance greater than its height, which is in fact little more than the adjoining buildings. This facade forms a striking closure to Brunswick Street which is virtually on its main axis. The interior has unfortunately been altered.

In Derby Square, the former St. George's Church was used by John Foster as the centre of an imaginative plan to create a circus as a cross axis between the newly widened Lord Street and Castle Street which extended south to his monumental Customs House. The Customs House, Lord Street/St. George's Crescent and South Castle Street were unfortunately destroyed by enemy action, the church already having been demolished in 1897, and post-war replacements have been a poor substitute for this grand conception; however (perhaps by divine intervention) the Victoria Monument survived. This was designed by E. M. Simpson, Professor of Architecture at Liverpool University, with the sculptures by Charles Allen, Vice Principal of the School of Art, and was completed in 1905. The four bronze groups around the memorial represent Agriculture, Commerce, Education and Industry, and there is a plaque recording the site of the Liverpool Castle. Castle Moat House on the north side of Derby Square stands on the site of the moat of the Castle. It was built in 1841 for the North and South Wales Bank and designed by Edward Corbett. The fine three bay, pedimented front has been brought forward and the giant composite pilasters substituted for original columns.

Returning along Castle Street, the west side presents a completely intact Victorian commercial street frontage. The end building, Bank Buildings occupied by the Midland Bank, displays the most exuberant of Victorian features with its elaborate entrance bay, balustraded iron balconies and carved reclining figures. This was designed by Lucy and Littler and built in 1868. The Scottish Provident Building, Nos. 52-54, is part of the late eighteenth century classical rebuilding of Castle Street which followed the widening in 1786. As can be seen from the remnants of the pediment on either side of Nos. 48-50, No. 46 is a further original portion, and in detail more complete. Nos. 52-54 have been much altered, with bay windows added, the central pilaster removed and the front refaced. Nos. 48-50, the building inserted between the earlier facades, is by Picton and was built in 1864. It is interesting that so scholarly an architect did not feel any necessity to relate his building to what would then have formed a regular street front. No. 44 is a later and eccentric nineteenth century replacement faced in ashlar and green vitreous tiles. The curious curved pediment contains a profusion of gilt foliate carving and bands of coloured tiles. Nos. 40-42, now occupied by the Burnley Building Society, are thought to be the work of Grayson and Ould. They are of four storeys, with three gables forming a picturesque roofline, and can be seen to their best advantage from Cook Street where they serve to close the view at the westerly end.

The Co-operative Bank on the corner of Brunswick Street, originally the Adelphi Bank, is the most inventive of this group. It was designed by W. D. Caroe, a highly original architect, and built in 1892. Contrasting bands ofgranite and sandstone and lively Victorian detail culminating in the corner turret with its unusual green copper onion dome give the building its distinctive appearance. Of particular quality are the bronze doors designed by the sculptor Stirling Lee showing historical pairs of inseparable friends. This incongruous subject was perhaps intended as a symbol for encouraging good relations with the bank manager.

At the top of Brunswick Street are two distinguished bank buildings. Barclays Bank was built as a private bank for Arthur Heywood and Sons in 1800. It has a plain five bay front with rusticated ground floor and blind arcading. Opposite is Halifax House built for the Liverpool Union Bank in a quiet palazzo style. The coat of arms on the Fenwick Street facade is inscribed with a date of 1835, though this is probably too early. The central round arched entrance is flanked by large windows each of which is divided by Tuscan pilasters with a frieze of triglyphs and metopes and a modillioned cornice.

The final block of Castle Street contains several Victorian buildings in the Loire style such as Nos. 34-36 which are again by Grayson and Ould. The corner into Brunswick Street is skilfully turned by the use of a round turret surmounted by a small dome. This is echoed on the Brunswick Street facade, the part between these turrets forming a steep gable elaborately decorated with a balustraded balcony, arcading, a carved frieze of ships and liver birds, and crowned by a niche. The National Westminster Bank Overseas Branch, another variation on the French Renaissance style, has an interesting variety of window types - second floor windows are ogee headed and cusped, third floor are narrow and round headed, and fourth floor are round arched. Tall clustered stone chimneys rise from the steep roof.

The next building, a further National Westminster Bank, was designed by Norman Shaw and built in 1899-1902 for the former Parr's Bank. Like the White Star Building it is striped, but otherwise it is not as striking. The massive round headed and rusticated entrance leads to a fine circular interior with central lantern and radiating coffered and carved panels with painted swags of fruit. In front of this building is a Sanctuary Stone embedded in the road surface. This is the only surviving mark of the boundary of the old Liverpool Fair held on July 25th and November 11th. In this area for ten days before and after each fair debtors were able to walk free from arrest providing they were on lawful business. Nos. 10-18 have a series of shops on the ground floor; the chemist's shop retains its original front. Above there is an irregular rhythm of windows, those on the second floor having panelled pilasters and pediments. Nos. 6-8, the United Kingdom Provident Institution, are distinguished by an order of giant Ionic columns to the third and fourth floors with a broken curved pediment. Finally, Nos. 2-4, another National Westminster Bank, are again in the Loire style and are richly decorated.

After the widening of Castle Street and the surrounding improvements at the end of the eighteenth century it was felt that the commercial community required better accommodation for transacting business. As a result, a new exchange was built on a large area that was cleared to the north of the Town Hall. Due to expanding trade, this building soon became inadequate and was replaced in 1862 by a larger exchange, designed by T. H. Wyatt in a French Renaissance style, this in turn being demolished to make way for the present building. Exchange Flags, created at the time of the first exchange, formed an open air exchange floor, and when in 1851 Queen Victoria looked down from the balcony of the Town Hall at the merchants assembled below, she is reported to have remarked that she had never before seen so large a number of well dressed gentlemen collected together in one place. In the centre of the Flags is the Nelson Monument, Liverpool's first public sculpture, erected in 1813. It was designed by M. Cotes Wyatt, with much of the modelling by Richard Westmacott, and shows four chained prisoners seated around a circular drum with relief panels and festoons. The drum was designed as a ventilator shaft for the bonded warehouse of which Exchange Flags formed the roof. These warehouses have now become a car park, but the monument still performs its necessary respiratory function.

Old Hall Street is named after the Old Hall, a thirteenth century mansion situated close to Union Street. Initially the seat of the Moore family, this house passed into the possession of the Earls of Derby in 1712 and was demolished for road widening in 182o. Old Hall Street had been a private road to the Hall, but after its becoming public, the northern end was developed up to the end of the eighteenth century, as the aristocratic part of the town. Here were leafy Ladies' Walk, Love Lane, and the promenade of Maidens' Green, all soon to be rudely destroyed to create an area of intense industrial and commercial activity and crossed by canals and railway tracks.

Much rebuilding has again occurred here in recent years, but there remains a group of good Victorian commercial buildings, the finest of which is The Albany Building situated a short way along Old Hall Street on the right. The Albany was built in 1856 for Richard Naylor, a wealthy banker of Hooton Hall, and designed by J. K. Coiling, a scholarly London architect. It is one of the best and earliest of the large Victorian office buildings in the city, successfully combining company offices with warehouse accommodation, a specific requirement of the cotton trade at that time. Before the cotton exchange was built adjacent, it formed the meeting place of cotton brokers who rented the offices. In style it is a very free Renaissance design with highly individual decorative treatment based on natural forms. This decoration can best be seen on window heads, tympana, frieze, and particularly in the fine entrance gates. The spacious courtyard is crossed by two elegant cast iron bridges, each approached by a delicate spiral staircase, and more ironwork can be seen in the ingenious top lit corridors which run the full length of the building.

Opposite The Albany is Harley Chambers, a classical neo-Greek style offiice building of 186o. The centre bay has a series of Venetian windows, that on the first floor has Ionic columns and a pediment. City Buildings, on the corner of Fazakerley Street, is a 1906 remodelling by Frederick Fraser of a mid-nineteenth century sugar warehouse. It is a spectacular job, the whole front being given a sheer cast iron and glass skin which sweeps around the corner in a manner used 25 years later by Sir Owen Williams in the celebrated Daily Express Buildings in London and a number of other principal cities.

The Cotton Exchange is another building that has been remodelled; however this recent refacing is an irretrievable loss, for the Old Hall Street frontage was the supreme architectural expression of the great power of the cotton trade and an extravagantly self-confident Edwardian Baroque design. Built in 1905-6 and designed by Matear and Simon, all that remains is the side and rear elevations. The one to Edmund Street is iron framed, with iron spandrel panels having delicate classical detail and large areas of plate glass rising through several storeys. The stone figures in front of the building on Old Hall Street represent Science, Industry and Commerce and were once part of the towers ofthe original frontage. Orleans House in Bixteth Street, also by Matear and Simon, is iron framed and clad in a similar manner to the Cotton Exchange. Liverpool has a strong and pioneering tradition of cast iron in buildings both as a structural and cladding material.

It is now necessary to cross Old Hall Street and follow the narrow Fazakerley Street and Rumford Place through to Chapel Street. The large modern development Richmond House stands on the.site of Richmond Buildings, which was a dignified palazzo style commercial block and probably the finest work of Picton. Fragments of this building can be seen in the first floor entrance hall. On the opposite side ofChapel Street is another fine building by Picton, Hargreaves Building, erected in 1861. This is a five bay Venetian palazzo with round arched windows and, in roundels above, busts of historical figures connected with South America. Adjacent to the Covent Garden facade of Hargreaves Building can be seen the rear of Mersey Chambers with aggressively projecting glass and iron oriel windows. This was built between 186o and 187o for T. and J. Harrison the Shipbuilders, and has a very different face on to Old Churchyard. Here note the carved Liver Bird over the central bay. The churchyard was laid out as a public garden in 1891 in memory of James Harrison, a partner in this firm.

At the south-west corner of the churchyard formerly stood the Merchants' Coffee House with a fine view of the river. In this meeting place were carried out the principal auction sales of property and ships. Similar gatherings were held at The Exchange Coffee House in Water Street, where, according to a notice in the Liverpool Advertiser in 1766, there was to be a sale of eleven negro slaves.

The Church of Our Lady and St. Nicholas is the parish church of Liverpool and was known as the Sailors' Church, St. Nicholas being the patron saint of sailors, and the tower being a landmark visible from the river. The tower is in fact the oldest part, for although the rest of the church was built in the fourteenth century as a chapel of ease, it was destroyed during the last war. The tower was designed by Thomas Harrison ofChester and built in 1811-5, replacing a previous tower with a spire which collapsed in 1810 killing 25 people including 17 girls from the Moorfields Charity School. Harrison's tower is a good example of early Gothic revival with flying buttresses supporting a graceful open lantern which is surmounted by a ship weather vane.

« Previous Top Home Next »