2 Alfred Warehouse 7 Albert Dock

8 Dock Traffic Office 9 Watchman's Hut

10 Wapping Dock Warehouse

11 Gatekeepers Lodge

12 Hydraulic Tower 13 Baltic Fleet Public House

14 Swedish Seamen's Church

With the spreading conflagration of the industrial revolution in Lancashire, Yorkshire and the Midlands, and the explosive growth of trade, particularly with the American colonies, Liverpool found itself in a position of unequalled strategic importance on the western seaboard. The ever increasing volume of shipping using the port and the relentless demand for berthing space which was to follow was matched by a continuous response by the Port authorities. It eventually took the form of seven and a half miles of docks and associated warehouses, on a scale which is still breathtaking. The use of brick, granite, timber, cast iron, steel and concrete reveals both the nature of the problems which were tackled and the development of technical solutions. The form and size of the successive works reflect the evolution of the design of shipping; from timber to iron, from sail to steam, from paddle to screw and, most significant, from small craft to the gargantuan vessels of the present day.

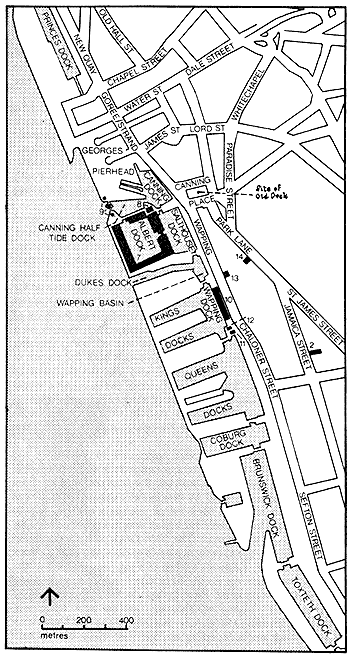

In 1708 Thomas Steers was appointed to advise on the building of the first dock. He recommended the abandonment of a former canal scheme and, instead, the conversion of the Pool into a wet dock controlled by floodgates. Although the idea of floodgates was not new, their use to enclose a harbour as was proposed was a bold invention which was to set the pattern for future docks the world over. The 'Old Dock' was completed in 1715 with an octagonal entrance basin and a small graving dock on the north side. Cadwick's Map of 1725 shows a pier at the entrance into the river no doubt to allow sailing ships to moor whilst waiting for a wind. By 1737, the dock was inadequate for the increasing volume of shipping and a new basin was constructed forming a large outer harbour to the Old Dock, with three graving docks opening on the west side. It was subsequently reconstructed in 1813 and named Canning Dock. A further dock authorised by the Act of 1737 was opened in 1753 and this was known as the 'South Dock' but was renamed 'Salthouse Dock' later in the century. Between this dock and the river were several shipbuilding yards. Salthouse Dock was reconstructed in 1845

The open harbour to the north was developed into 'Georges Dock' which extended from James Street to Chapel Street and which was opened in 1771. The dock was able to accommodate the new larger vessels requiring greater draught, and parti-cularly Man-of-War ships. It was reconstructed and further enlarged between 1822 and 1825.- Facing on to the dock, between The Strand and Goree, stood the great arcaded Goree Warehouses, built in 1793, reconstructed in 1802 after a disastrous fire, and finally destroyed in the blitz in 1941.

By 1785, the volume of shipping had increased to such an extent that two new docks were proposed to the south of Salthouse Dock. King's Dock opened in 1788, and Queen's Dock which was completed in 1796 and considerably enlarged in 1816. Both docks were originally separated from the docks to the north by the entrance section to the proposed Runcorn Canal. The Duke of Bridgewater had obtained powers under Act of Parliament in 1759 for the construction of the canal which was to have provided a link between the port and the rich salt mines of Cheshire. A terminal dock and outer channel were opened in 1773 and the old salt works, after which Salthouse Dock took its name, stood alongside. This problem of separation was not obviated until the construction of Wapping Basin in 1858, which entailed the reconstruction and narrowing of King's Dock in 1852.

Parallel to the dock road behind Queen's Dock is Jamaica Street, which runs through an area containing many fine examples of nineteenth century warehouses including the Alfred Warehouses.

1 Lower Bank View Warehouse

3 Fairie Sugar Factory

4 Dock Wall

5 Waterloo Dock

6 Galton Street Warehouse

15 Two entrances to Stanley Dock

16 Stanley Dock Warehouse

17 Stanley Dock Hydraulic Tower

18 Stanley Dock Tobacco Warehouse

19 Stanley Dock Bonded Tea Warehouse

20 Entrance to Leeds Liverpool Canal

21 Two Canal alocks

22 Victoria Tower

23 Watchman's Hut

24 Dockmaster's House

25 Sea Wall

In 1800, the number of ships entering the port was 4,746 with a tonnage of 450,000. The docks and basins enclosed some twenty-six acres of water. A hundred years previously there was only the open river and meagre harbour facilities. The number of vessels entering the port then was 102 with a tonnage of 8,619.

The eighteenth century had been a turbulent one, with civil rebellions and foreign wars, with press-gangs in the streets of the town and privateering on the seas. Liverpool merchants grew rich on the profits of the slave trade and the rapidly expanding commerce with the West Indies and North America. Ships which sailed out of Liverpool, laden with goods from the awakening industries of the hinterland, returned with tobacco, rum and sugar, and, in the latter part of the century, with cotton. By I 800, the anti-slavery movement was in full flight and threatened the port with ruin. But the momentum which had built up in the eighteenth century was not to be stopped. In the century which followed, as mines, mills, factories and furnace chimneys transformed the Midlands and the North of England so the almost continuous work of building docks of ever-increasing dimensions progressed in Liverpool. Canals and railways were cut through to the port. Emigrants to the New World from all over the country and Europe thronged the streets and quays.

The prodigious expansion of the port was matched by the growth of the town. Between 1831 and 1891, the population within the boundaries of the town alone trebled, from 205,572 to 617,032.

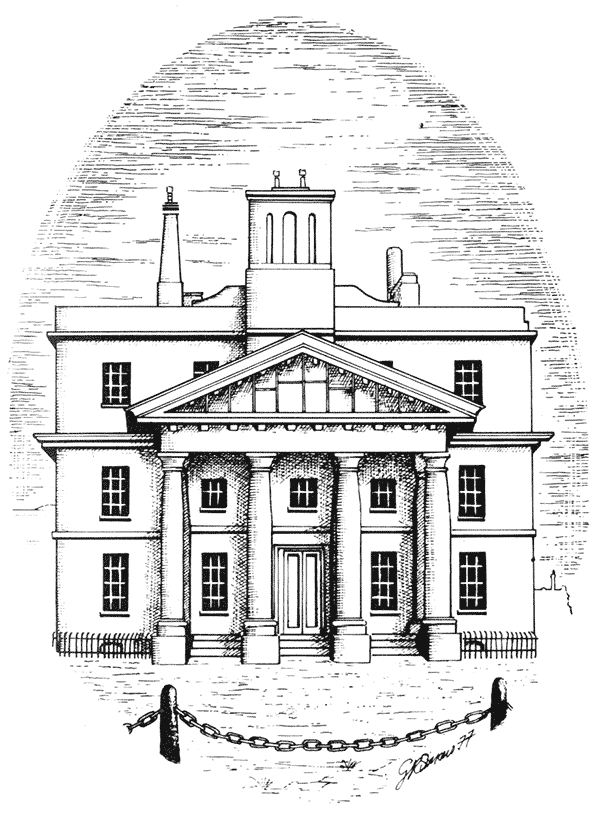

In 1811 an Act of Parliament was passed for the filling in of the Old Dock and the construction of Prince's Dock to the North of George's Dock. Built by John Foster and his son, it was opened in 1821 and was the first of the docks to be enclosed by walls, an arrangement which was subsequently employed throughout the dock system. Prince's Basin was re-modelled in the 186os and converted to a half-tide dock with three outer entrances. At the North entrance, a great brick octagonal tower was constructed to house the hydraulic equipment which powered the dock gates. The tower rose out of a spreading base with clock faces in four of the sides of the superstructure. Crowned by a deep machicolated battlement, it was surmounted by a slated conical roof with dormers and iron cresting. Together with several similar towers which punctuated the outer lines of the docks, it has now been demolished. Because of vehement opposition and continuing demand for dock space, the Old Dock was not cleared of shipping until 1826. The Custom House which was built on the site between 1828 and 1839 to the design by John Foster the younger, was undoubtedly the finest building in Liverpool destroyed by bombing in the second World War.

In 1816 work commenced on a small dock to the south of the Queen's Dock known as Union Dock, together with its large outer basin. The two were united in 1858 with gates opening directly into the river and the new dock so formed was named Coburg Dock.

In 1824, Jesse Hartley, bridgemaster for the West Riding of Yorkshire, was appointed engineer to the docks. He was a man of enormously powerful vision who carried out his concepts with strength, solidarity and skill. Granite brick and cast iron were the materials in which he delighted to work and in which he expressed his genius, his integrity and stern independence.

The first of his works to the south, Brunswick Dock and half-tide basin, was opened in 1832. Built for the timber trade, the eastern quay was sloped to facilitate unloading. The dock and basin were built on a new massive scale, enclosing twelve and two acres of water respectively. Two large adjacent graving docks were also added. To the north work went ahead at the same time on Clarence Dock which was opened in 1830.

Designed for the new steamers, the dock was laid out some distance to the north of Prince's Dock to avoid the risk of fire. It was the first to incorporate continuous covered sheds and this facility was later provided round the older docks. Waterloo was later reconstructed with inner and outer docks. Warehouses were constructed on three sides of the inner dock and were completed in 1867.

Close by on the dock road, between Barton Street and Galton Street, here called Waterloo Road, are examples of nineteenth century warehouse building.

The Victoria and Trafalgar Docks, which completed develop-ment between Clarence and Waterloo, opened in 1836. Both were built for powered vessels owing to the great increase in the use of steamers.

In 1845, the Prince Consort opened the Albert Dock, surrounded by its warehouses on a massive scale. Previously no warehouses had been provided within the Dock Estate although as early as 1803 the desirability of integrating warehousing and docks had been debated with the mercantile associations of the town. In 1810 plans for docks enclosed by warehouses had been prepared, but in the face of strong opposition from the warehouse owners in the town, the Bill for implementation was rejected by Parliament. Because of the lack of secure bonded warehousing in the town, to meet the requirements of Customs and Excise, a commission was set up in 1821 which recom-mended the provision of warehousing adjacent to the docks separated from areas of public access by walls or other means. At a blustery meeting at the Town Hall it was again argued that the proposals would be ruinous to the warehouse owners. The value of the warehouses within the town at that time was estimated at £2 million. The matter was again left in abeyance until 1837 when the Municipal Council, as owners of the docks, resolved to proceed despite continued opposition and in 1839 Jesse Hartley produced designs for the Albert Dock to the river side of Salthouse. The plan was agreed in 1841 and parliamentary sanction gained.

« Top »

In 1846, the year after the completion of Albert Dock, work commenced on the enlargement of Salthouse Dock and the construction of Wapping Dock, to the east of King's Dock. The new and the enlarged docks were connected by a cut behind Duke's Dock, which had been the entrance to the Duke of Bridgewater's Runcorn Canal. These works entailed the removal of much valuable property fronting on to Wapping and the construction of a new road set back from the old line. It was a long job and Wapping Dock with its fine warehouses was not occupied until 1858.

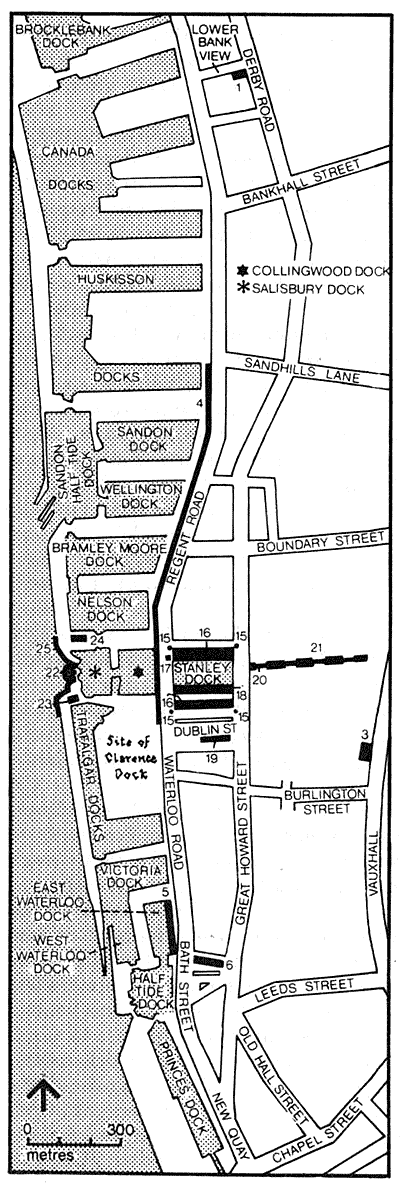

In 1846, the year after the completion of Albert Dock, work commenced on the enlargement of Salthouse Dock and the construction of Wapping Dock, to the east of King's Dock. The new and the enlarged docks were connected by a cut behind Duke's Dock, which had been the entrance to the Duke of Bridgewater's Runcorn Canal. These works entailed the removal of much valuable property fronting on to Wapping and the construction of a new road set back from the old line. It was a long job and Wapping Dock with its fine warehouses was not occupied until 1858.Meanwhile, 1848 saw the opening of Salisbury, Collingwood, Stanley, Nelson and Bramley-Moore Docks to the north. With the development of steam ships, the protected outer basins were no longer required and it was possible to open gates directly into the river.

The Stanley Dock is the only inland dock in Liverpool, being on the landward side of the dock road, here known as Regent's Road. It is enclosed to north and south by warehouses.

Stanley Dock, which provides access into the Leeds-Liverpool Canal is linked to the Collingwood Dock by a channel traversed by a lifting road bridge and thence to Salisbury Dock. Between the paired entrances to the river from Salisbury Dock stands one of the several great castellated towers which were built by Hartley to house the hydraulic machinery for the operation of the locks.

The following year, 1849, the Sandon Dock was completed and later modified following the Act of 1891. Huskisson Dock, opened in 1852, was subsequently extended eastwards in 1860. It reflects the rapid increase at the time in the size of vessels. The two graving docks were 950 feet in length with the provision of hydraulic lifts whereby ships of 500 feet could be raised bodily above the water.

There followed two major controversies. Firstly, an application to Parliament made in 1855 for the further expansion of the dock system and the provision of additional warehousing met with vehement opposition from a lobby of the almost bankrupt Birkenhead Dock Company. As a result, the main aims of the Liverpool Bill were defeated, and in the same session an Act was passed whereby the undertakings of the insolvent Company were transferred to the Liverpool Corporation, which agreed to purchase the property.

Secondly, in 1857, after a long and bitter contest, a Bill was introduced to the House of Commons for the transfer of the dock estate from the Corporation of Liverpool, which until this time had developed and managed the port, to an entirely new body of trustees. The ostensible promoters of the Bill were the Man-chester Chamber of Commerce, the Manchester Commercial Association, and the Great Western Railway Company who had long resented Liverpool's right to levy town dues on cargoes passing through the port, a right established by King John and purchased by the Corporation in 1672. The Bill was passed by the House of Commons but amended by the House of Lords whereby £1.5 million compensation should be paid to the Corporation. As a result, the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board was established.

As the timber trade increased, for which the Queen's and Brunswick Docks had been constructed, it was decided to build new facilities to the north. Canada Dock was opened in 1859 with extensive timber yards. Later the half tide dock was extended to the north in 1872, giving access to additional docks to the east as far as Regent Road. The Canada Docks again established a new massive scale previously unseen. The increasing size of shipping, and the girth of the paddle steamers in particular, dictated that two of the entrances to Canada and Huskisson Docks were of 80 feet in width and one of 100 feet. The enormous gates were operated by hydraulic machinery housed in Hartley's magnificent double octagonal castellated tower of granite, which has now been demolished. The abandoning of paddle steamers for ocean going in favour of screw driven ships rendered these facilities unnecessary for many years to come. A further branch dock was added in 1896, together with graving docks alongside of 926 feet in length.

Opposite the Canada Docks is a street called Lower Bank View, in which can be found further examples of nineteenth century warehouses.

At the south end, the Herculaneum Dock was opened in 1864 with its extensive graving docks. It was later extended and improved in the 1880s.

By 1872 dock provision was again inadequate for the ever increasing demand. Plans were prepared in that year by G. F. Lyster, who succeeded the two Hartleys, father and son, as engineer to the Dock Board, for seven new docks beyond Liverpool's northern boundary with Bootle. The plan also proposed two new docks to the south, and Langton and Alexandra Docks were completed in 1881. Harrington followed in 1883 and Toxteth in 1888.

In parallel with the commercial expansion of the port, the increase in passenger traffic in the nineteenth century was prodigious. In 1847 a floating landing stage off St. George's Parade was built by L. Cubitt, engineer. Supported on iron pontoons, the stage was 500 feet long and 80 feet wide.

In parallel with the commercial expansion of the port, the increase in passenger traffic in the nineteenth century was prodigious. In 1847 a floating landing stage off St. George's Parade was built by L. Cubitt, engineer. Supported on iron pontoons, the stage was 500 feet long and 80 feet wide.It was rebuilt in 1873-4 and extended to 2,063 feet. In 1896, it was again extended by a further 400 feet with an additional jetty at the north end of 350 feet, giving continuous linear berthing of over half a mile. High level covered pedestrian bridges, adaptable to allow direct linkage to the liners, connected to an array of customs and baggage halls and waiting rooms.

Mechanical luggage conveyors linked from the stage and the holds of the liners to the passenger complex. In 1895, Riverside station opened which allowed passenger trains to stand along the quayside under cover and contiguous with the covered Princes Parade where carriages, cabs, and later, taxis could queue. In 1893, the world famous overhead railway, which ran parallel to the dock road for seven and a half miles from Seaforth in the north to Dingle in the south, was opened. At the close of the century George's Dock was drained and filled and the Pier Head area was formed..

The Lower Bank View Warehouse is dated 1885 and is on seven storeys, principally of red brick. The windows have segmented arches with small panes set in iron glazing bars. There are six recessed loading bays with round arches in blue brick and iron doors.

The Alfred Warehouses form a large square block between Jordan Street and Bird Street. Built in 1867 and extended in 1879, the building is of brick articulated by the use of blue brick. The warehouse accommodation is on five storeys and a basement and hoists are provided on the side elevations. All the windows are small with segmental heads and the building has a cornice and parapet with a central gable and 'eye'.

The Fairie Sugar Factory is some distance from the docks in Vauxhall Road. The warehouse block is dated 1847 and is of red brick. It has a very high ground floor with five floors above and a tower projecting above the roof line to the north-east. There are eight windows with segmental heads on each floor with small pane glazing. The later buildings to the south are not listed.

The Dock Wall from opposite Sandhills Lane to Collingwood Dock with the entrances was the work of Jesse Hartley. The wall itself is of large irregular shaped blocks of granite and is about i 8 feet in height. It incorporates large carved plaques with wording such as 'Sandon Graving Dock 1848' and 'Collingwood Dock 1848'. The wall is punctuated by massive gate posts and turrets at the entrances. The main entrance to Sandon Dock has two large square stone piers with cornices and iron lampholders and in the centre is the gatekeeper's lodge with its cornice and parapet, ornamented at the corners. The nameplate on the front is in a pedimented panel and the lodge has a central chimney. The vast wooden doors to the entrance were designed to slide back into the thickness of the wall. The entrance to docks 47, 49 and 50, opposite Boundary Street, has three round, tapering turrets with heavy tops and deep slits at the side to receive the gates. The former entrance further south is similar but the centre turret is oval in plan. The entrance to North Collingwood, North Salisbury and Nelson Docks again has three towers, but the centre one is taller and larger. The entrance to Nelson, South Wellington and Bramley-Moore Docks, opposite Fulton Street, is similar, as is the now blocked entrance near Bramley-Moore pumping station.

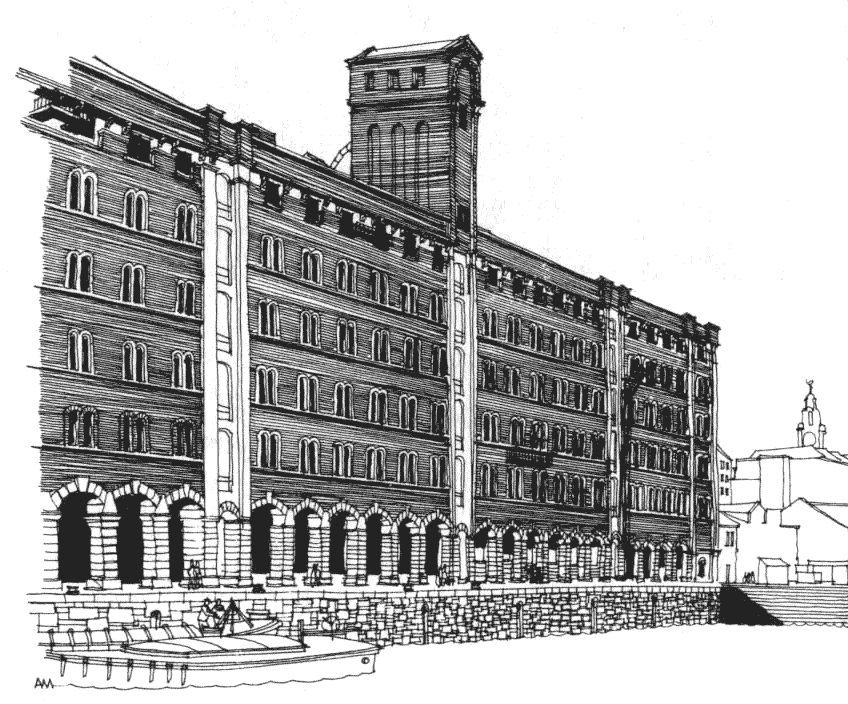

The Waterloo Dock Warehouse was built in 1867 by George Fosbery Lyster as a grain store and it incorporated machinery for raising, storing, turning, ventilating and discharging the grain. The ground floor is an open arcade supported by rusticated granite piers and arches with five vaulted floors above. The structure above the ground floor is of brick and the openings in each storey are double windows with semi-circular heads on four floors. The cills of the windows are formed by continuous rough stone string-courses. The buildings are surmounted by a bold cornice carried on stone brackets and a parapet above. The windows of the top floor are single, the cornice forming a continuous lintel. Hoisting machinery is housed in turrets which rise above the general line ofthe structure.

Galton Street Warehouses. These brick warehouses, dating from about 1870, form a group on the north side of Galton Street. At the corner of Waterloo Road stands a seven-storey warehouse with round-arch doorways, windows with vertical iron bars and stone lintels and recessed loading bays. The warehouse between Greenock Street and Glasgow Street is of five high storeys and that to the east of Glasgow Street is of six storeys. The cobbled roadways forming Galton and Greenock Streets are also worthy of note.

« Introduction Top Home Next »